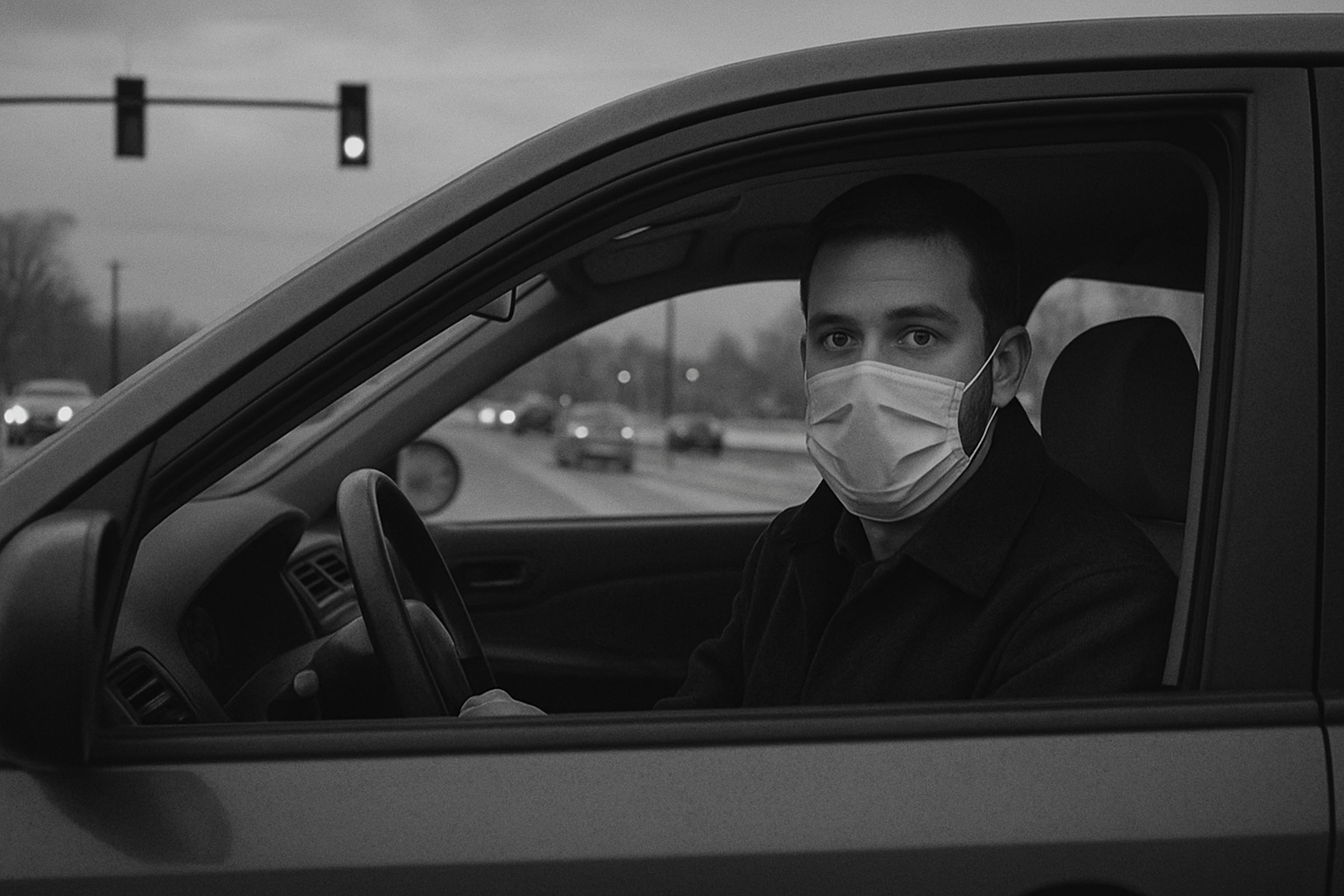

I don’t remember where I was on 9/11—too young, not yet politically engaged—but I remember where I was on January 6 of 2021. Fayetteville, Arkansas. The corner of North and Garland—my wife used to call it Garlic—Avenue. Traffic scudded on the four-lane road beyond the windshield, past the pallid glare of half-reflected winter sky. On my phone, bodies massed on the steps of the capitol. Barricades buckled. Pepper spray. Batons.

My neighbor had landed herself in hot water. While sticking tiles onto wooden tabletops, one of her pandemic hobbies, she’d gotten grout under her nails. Now her nailbeds were infected. She’d called me from the yard we shared and begged for a ride to the clinic.

I’d watched her through the window, breath and cigarette smoke clouding thickly around her mouth. From one ear, a mask loop dangled.

The doctor she’d wanted to see was known in Northwest Arkansas for making healthcare available to undocumented patients and refugees. My neighbor was neither undocumented nor a refugee, but she was studying immigration law and had intense convictions. True believers put their faith in other true believers.

I suppose that’s also why she put her faith in me. Two and a half months earlier, when the president had contracted COVID and been rushed to Walter Reed, I’d felt a surge of vindication. Finally, the hour had come. I might look like the people who chanted his slogans and took his dewormers and drank bleach in his name, but I was not one of those people. I kept my distance, wore my masks, believed in science, doctors, medicine, and fetishized the thought that I might also do no harm. I might be white, I might be straight, I might be male, but I was not like them.

Then the unexpected happened. The unexpected hit me like a gut punch through the screen: that vindication once again, still more righteous this time, more exhilarating. Those motherfuckers who’d lied to us, cheated us, sold us out, stolen our futures, wallowing up there in their swamp and sucking us dry for years, were finally getting what was coming to them.

The barbarians were at the gates. It made no difference that my body was in Northwest Arkansas. My heart was with them.

Behind my mask, a blush of pride.

* * *

“A blush of pride.” I borrow the phrase from Ayad Akhtar’s 2012 play Disgraced, in which his protagonist, a Pakistani-American lawyer, confesses to feeling “a blush of pride” in response to 9/11.

In Mohsin Hamid’s 2007 novel The Reluctant Fundamentalist, Princeton-educated Pakistani financial analyst Changez puts it this way: “Despicable as it may sound, my initial reaction [to 9/11] was to be remarkably pleased.” Elsewhere in the novel, he declares, perhaps sincerely, “I am a lover of America.”

In his ferocious, sprawling, autofictive masterpiece Homeland Elegies (2020), Akhtar returns to this refrain. His avatar is haunted by the fallout from his fictional lawyer’s confession. He struggles to articulate for us, and possibly also for himself, the degree to which that “blush of pride” derives from his own complex emotional response to those attacks—as a writer, as a New Yorker, as a non-practicing American Muslim, as a human being.

Changez’s opposition to the predatory system of extractive American capitalism—or, depending on how one reads the novel, to America’s monopoly on that system—stems from his firsthand experience of the socioeconomic damage done to developing nations by the whims of Western finance. For Akhtar, who is not Pakistani but Pakistani-American, the wellspring lies in the domestic corollary to that damage, the wreckage wrought by neoliberal policies upon the American heartland. “They had good reason to be scared and angry,” he writes. “They felt betrayed and wanted to destroy something. The national mood was Hobbesian.”

That he uses “they” here, not “we,” hardly matters. He understands.

* * *

The doctor might’ve been a true believer, but he’d never gotten certain memos. “Heard he’s prescribing ivermectin,” my landlord told me some weeks later. “Says it’s not political. He just wants to help people.”

My landlord was another true believer, but I couldn’t tell, from the way he delivered this news, where he stood on ivermectin. I knew exactly where my father stood because he sent me links and screenshots every night: most recently, a reddit thread where COVID dissidents were sharing ivermectin stories. Of particular interest to my father were their graphic and grizzled laments about one of the drug’s common side effects: explosive diarrhea.

“Time to flush out all the maggots,” he declared—or something like that. I can’t find the thread to quote him.

I know he called them maggots, though, and not for the first time—punning on MAGA, and maybe also on ivermectin’s long and well-attested history as an antiparasitic, but there was something in that word that didn’t sit quite right with me, true believer though I was.

Maggots.

Cockroaches.

Parasites.

Vermin.

Not the Tutsis, this time. Not the Jews. The white folks. Not all the white folks, either: just the anxious, harried, desperate, disillusioned white folks. Just like him. Like me.

* * *

I make sense of the world through fiction because I trust fiction. I read nonfiction, too, but I don’t trust nonfiction, which wants too much to be believed. I don’t trust anything that wants too much to be believed. Those who want to be believed will do whatever must be done, will cook the books and rig the game and paper over truths, to pass the litmus tests deployed by narrow minds: their readers’ and their own.

“Fiction,” I say to my wife, “is the only place where you’ll find any truth these days.”

“No,” she says. “You can’t always look to fiction for the truth.”

“I’m not saying fiction’s always true. I’m saying it’s the only place where truth can go to hide.” Why else would Akhtar call his memoir autofiction? What the hell is autofiction?

“Not really,” she says. “What about your firsthand experience? Experience comes before fiction.”

“Some people’s experience. Not mine.”

Not Akhtar’s, either. Not Hamid’s. I’m white, I’m straight, I’m male, but I’m not like the people swarming on the capitol steps that day—except for when I am. Akhtar and Hamid are brown men, Muslims, Pakistanis, but they’re not like those jihadists on those planes—except for when they are like them.

“You’re the one who’s got to make your experience count,” my wife tells me. “You’re the one who’s got to make your experience matter.”

When I say fiction, I mean that interstitial space, that twilight zone, that conscience-haunted in-between—what remains of it, anyway—where experience matters. Can matter.

Even theirs, post 9/11. Even mine.

* * *

In one of Homeland Elegies’ most poignant strains, Akhtar writes of his father, a cardiologist who lives in the United States, who personally treated Donald Trump for several years, and who develops with the man a strange infatuation.

Both Trump and the elder Akhtar “binged on debt in the ’80s” and met “as each was coming out from under virtual financial ruin,” but there’s more to link these two men than their shared insolubility. Both are hardheaded and take visceral pride in their well-defined views of the world. Both are larger-than-life. Both are showmen. In the lead-up to 2016, Akhtar becomes aware of the enormous, hidden reservoirs of racial, sexual, and nationalistic bigotry that his aging father harbors, directed both outward and inward. To crown his biting commentaries on the whites, blacks, Jews, and women, the elder Akhtar adds, with a flourish, “that Muslims were backward because the Quran was nonsense and the Prophet was a moron.”

In another text thread that I’ve lost, my father referred to Missouri, where his family’s lived for generations, as a cesspool. The region was still reeling from a flurry of tornados, which had demolished many homes, but as with the Tennessee floods, and the California fires, and the dust storms sweeping central Illinois, he took this catastrophe as one more vindication. “Another manifested visualization,” he wrote of the dust storms, which caused several car crashes, many fatalities. “We’re winning!”

I recall the word cesspool because it’s hard not to; but it’s his other words, individually benign but collectively less so, that really crank the passive aggression up past ten. Paraphrasing cannot adequately capture what it’s like to get a message from my father. Each of his expositions hits you like a caustic little puff of ozone, a desiccated husk of rage that crumbles into chalky dust—flammable, suffocating—at the first sign of opposition. With him, the ground is always shifting, the bounds of acceptable speech are never where you thought they were, the goalposts are always somewhere else on the field. For several months, he communicated only by sending me music, darkly haunting songs. One evening, I answered with the Cantigas de Santa María, eliciting this response:

“Random. Let’s see: I don’t understand the lyrics, never bothered to look into a translation, and think that style of medieval music is more creepy than most other music from that time.”

I asked him which medieval music he considers un-creepy. He sent me a six-minute video in which Iranian whirling dervishes sing and dance themselves into trances, then hammer knives into each other’s skulls.

Still hoping to land on his wavelength, to humor his indiscriminate cynicism, I replied, “Meanwhile, Metallica is releasing a full album in ASL. *Sigh.* Such liberal decadence has beset the Western World…”

“Yeah,” he answered, “but without liberal decadence, we wouldn’t all be preserving every dog turd in forever plastics. How could the future manifest without that crucial component?”

There’s no keeping up with him. I don’t think he even keeps up with himself anymore. Even before the pandemic, he slept all day, drank, smoked, and watched the news all night, and had to fight off regular attacks of chronic pain. At some point, he flipped the world map in his hallway upside down—maybe just a nod to the arbitrary Eurocentrism of modern cartography, or maybe something more. Undiagnosed mental illness runs deep on his side of the family: alcoholism, depression, and bipolar disorder. He did a lot of drugs in college, smoked a lot of weed. He was a true believer then, scorning the mainstream, aligning himself with the counterculture, pouring his body and soul into the organics movement only to see the whole thing commandeered by corporate interests just a few years in, one more mile marker on the road to this dystopian here and now where everything is toxic, everything, the denouement of Akhtar’s “conquering rise of mercantilism, with all its attendant vulgarity, its acquisitive conscience supplanting every moral.”

What’s left to hold things together? To anchor the soil of this postmodern wasteland? What’s the point of choking out your demons, of bothering not to despise one another, not to dehumanize those tribes with whom you constitutionally disagree when, with all forever these chemicals coursing through our veins, most of us are hardly even human anymore, and anyway, even if we were, it’s not as if you really expect such goodwill in return?

* * *

Remember that this is nonfiction. Remember that nonfiction, while maybe not the same as propaganda, does grow from a common seed. Remember that nonfiction is the well-lit public space that smells of bleach and rubbing alcohol, where you’re compelled to bury most of what you are beneath the true believer that you think you are, or want the world to think you are, or convince yourself you are, or convince yourself you could be.

Remember that fiction is the candlelit space where there’s room to maneuver. To breathe. To loosen your belt, inhale, and feel yourself expand across the spectrum of potentials, possibilities. To be.

Fiction is the improbable space where a cardiologist from Pakistan can turn out to be the soulmate of an American real estate mogul and reality TV star turned politician. Where a Pulitzer-prize-winning writer named Ayad Akhtar can be like himself one minute, like one of his fictional characters the next. Where a Princeton graduate and advocate for Pakistani self-determination can be a terrorist and also not. Where a person can be many things at once, all those selves shoving and jostling, trampling one another, seething, hissing, snarling, shouting, yelling stupid slogans, yearning to break free.

Remember that nonfiction is the space where you can still be good.

You know you want to be.

Remember that this is nonfiction. Remember, when I tell you that you haven’t met the man who raised me yet, that this isn’t fiction, even autofiction. Believe me when I tell you that you haven’t glimpsed the man who said to me, “Not everyone’s the same, but we’re all of equal value. That’s the same.” Who taught me to treat everybody with respect and dignity regardless of color and creed. Who displayed the same charisma at the office and the grocery store, where he used standard English to chat with clients and cashiers, and also while talking to one of our neighbors in an Appalachian brogue so strong that I could barely understand. Who once made a phone call on behalf of our other neighbor, a Korean florist, and had to explain to the woman on the other end, when she asked why he was there, about the neighbor’s English, only to realize, too late, that the words he used—“not so good”—had hurt the florist’s feelings, prompting him to feel sincerely sorry, to do his best to make amends.

You still don’t know the man who told me once how strange it was to realize that his parents, who’d taught him to treat everybody with respect and dignity regardless of color and creed, never really believed in that ideal themselves.

This is nonfiction, remember. Don’t believe what you read.

* * *

We’re not so different, us and them—and it hardly matters who you mean by “us” and “them.” We all know what it means to hurt. To bleed.

We all know what to do to hurt each other when the time comes. There’s a word for knowing what to do to hurt each other when the time comes: empathy.

Maybe that’s why my father likes watching those whirling dervishes hammer knives into each other’s heads. They’ve figured out how not to hurt, how not to bleed.

Maybe he wants in on that secret.

Maybe.

I remember where I was on January 6 of 2021. I was sitting in my car, I was alone, and then, for a few fleeting moments, I was part of someone else’s fiction, someone else’s dream. The American Revolution 2.0, livestreamed direct to video this time—there is a word for this one, too: democracy—but then CNN pulled me back into nonfiction.

“It’s only now becoming clear to us how close this was. How bad it could’ve been.”

I remembered that I was a true believer.

I remembered who was “they” and who was “we.”

I remembered that nonfiction is the safe space where you get to prove that you are not a maggot, not a cockroach, not a parasite, not a dissident, not an anti-vaxxer, not a terrorist, and not a threat. The space where you can still be good.

You know you want to be.