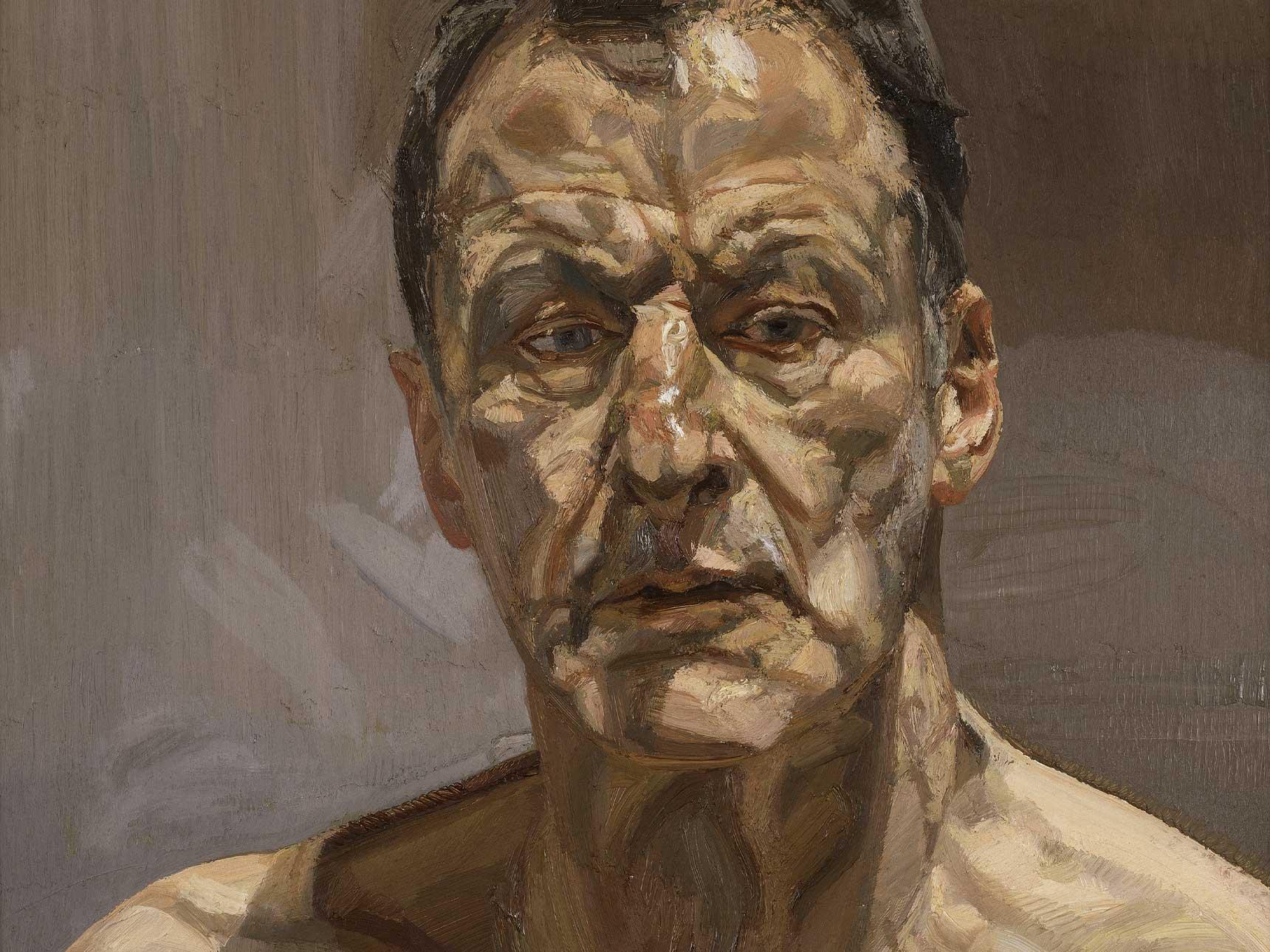

Through a close examination of Lucian Freud’s portrait paintings, this essay elaborates on the concept of violence embedded in looking, drawing parallel between his work and Simone de Beauvoir’s A Very Easy Death. It then suggests a specific definition of monstrosity in discussing the relationship between the observer and the observed, demonstrated through the extreme example of the onlookers and the executioner watching a prisoner undergoing lingchi, death by a thousand cuts. The essay ends with a return to the idea of “horror”: painting and writing, among other practices, are means by which we wrestle with our horror of the unstoppable passage of time.

“All men must die: but for every man his death is an accident and, even if he knows it and consents to it, an unjustifiable violation.”[1] So says Simone de Beauvoir’s concluding remark of A Very Easy Death, which is a textual documentation of events preceding her mother’s death. Her mother was seventy-eight at the time, suffering from cancer. Death, as the common word of comfort puts it, would bring her to another world where she was free of pain. In Beauvoir’s confession of her own change of attitude towards death, I find resonance of words we frequently encounter after the passing of someone elderly:

I did not understand that one might sincerely weep for a relative, a grandfather aged seventy or more. If I met a woman of fifty overcome with sadness because she had just lost her mother, I thought her neurotic: we are all mortal; at eighty you are quite old enough to be one of the dead…[2]

It was only after her mother’s death, having witnessed it from a close distance, that her thought changed. She came to realize that one had to die from something.[3] The “something” never consists of old age alone, and in this sense the knowledge that as one ages one’s life might end soon is insufficient to lessen the horrible surprise when it actually happens. It is, still, a total deprivation of both the dead and those who survive.

As much as the occurrence of death, I believe that what led to this change of attitude was also the (physical and mental) closeness between Beauvoir and her mother, especially during the time when her mother’s condition worsened and death approached day by day. Reading this book, doubtlessly the thinnest of hers, I think of Susan Sontag’s claim that perhaps the only people with the right to look at images of suffering of the extreme order are those who could do something to alleviate it, or those who could learn from it; the rest of us are voyeurs, whether or not we mean to be.[4] Although she is talking specifically about the case of photography, I believe the kind of shame Sontag attributes to looking at the close-up of a real horror is transferrable to the experience of viewing other forms of art. Regardless of their formal differences, all such representations facilitate an unusually intimate encounter between the viewer and someone else’s suffering. This encounter begs the question: why do you keep watching? Why can’t you avert your eyes and look away? Why won’t you? Sontag describes the tension between one’s helplessness in the face of other people’s pain and the desire to look on. Here it should be noted that, by “suffering of the extreme order”, she is referring to the cruelty of war. She herself adds that suffering from natural causes, such as illness or childbirth, is scantily represented in the history of art; that caused by accident, virtually not at all.[5] Looking at The Painter’s Mother, Dead, a graphite drawing done by Lucian Freud (1989) right after the moment when his mother passed away, what I have in front of me is precisely that which is “scantily represented”, a document of the familial trauma that belongs to the same category as A Very Easy Death. In situations like this, the one who documents will probably find themselves wondering about those very same questions on looking, not only because there is nothing one can do to help, but also due to the intimate nature of the events. Now, alongside the progress of illness and ageing and the affects they brings about, the writer/painter is introducing their own subjectivity into the represented event as well, while occasionally the experience of the narrated person recedes to the background, since essentially what we are seeing are traces left by the documenting hand, not by the person to whom everything actually happened. Under such a circumstance, what does it mean to keep documenting? What is happening, then, when such documents are made public?

Such were also the questions I asked myself when, during the time when my grandfather was going in and out of hospital almost every day, I found myself revisiting Lucian Freud’s portraits for solace. Maybe it was because his work, with its brutal intimacy first manifested in all the intense painting sessions, ultimately reveals a very specific form of naked truth about the human subject;[6] or, to make it less absolute, a certain form of truth embodied in the sitter, denoted by his honest rendering of everything right there in front of his eyes—the face, the fingers and toes, the way a full head of hair takes the shape of some unruly wire sculpture. There is, however, something inherently paradoxical in such a mode of working, for although we as viewers are aware of the painstakingly long duration of time spent on the portrait before our eyes, what we perceive from the canvas is inevitably nothing but an instant. It is a flattening of time, hours of time dispersed throughout days, weeks, or even months, condensed into this particular instant, when the body happens to assume this particular posture, since we know that, in reality, those limbs could and almost certainly did move the next instant, making its precedent forever lost and gone; if the body so much as quivered, the previously established composition would be altered. To paint in the way Freud does, always from life, from infamously long sessions with his models, to desire that form of truth he so desires from his practice, is simultaneously to mimic death and facilitate its delay. It is a desire that keeps returning the body of the sitter to its previous gesture, the past, and by doing so entraps the body in a present constructed according to the will of the painter: a desire with no future. In this sense, to paint the truth of the sitter is to desire them onto their death—if only temporarily.

Within our own family we have witnessed how illness, as a radical transformation of the patient’s old form, may create an encounter between those close to the patient and the patient as a body that has gradually become strange, if not unrecognizable. It calls to mind the concept of monstrosity, in the sense that not only the incurable disease inside one’s body but the body itself as well is often understood, both metaphorically and literally, as an untamed monster. Yet still, what exactly is monstrosity in this case, and what makes a body monstrous? Witnessing, viewing, and reading tales of ailing bodies, I see that the monstrous body is one that defies its supposedly natural relation to time, and in doing so also distorts every other body’s relation to time. Such a distortion is deeply horrifying, since it erases the present as we know it and instead conjures up a new present by drawing a definition from the reality of this strange body that confronts us, the patient included; this new present becomes all what we experience. A non-monstrous body lets go of time and situates itself within its flow, while a monstrous body assimilates time inside itself, refusing it, flattening it—it is in this sense that every body painted by Freud is a monster. Each of those bodies symbolizes the sick body in its own way, affected by a disease that cuts it off from the flow of time and returns it to unpredictable points in the past which now overwrite both the present and the future. Monstrosity happens when the chaotic overflow of time somehow refuses to spill from its container, the body, leaving it intact with an inner swelling that sometimes, but not always, manifests on its appearance. Regardless, such a body occupies a space easily beyond the reach of the ordinary. The moment when a viewer lays eyes on the painting simultaneously consolidates a monstrous form and undoes their own bodily boundary which guards their initial understanding of, and relation to, time. Such a moment is sensual, because it rejects the common logic. By way of this rejection, it further demands a new language.

* * *

There used to be a form of torture and execution in China called lingchi, known as slow slicing or death by a thousand cuts. Translated literally, ling means to draw near, and chi means slow, late. Simply put, it is a method aimed at the prolonging of a person’s agony as death approaches cut by cut. In The Tears of Eros, Georges Bataille writes about his photograph of a prisoner undergoing lingchi.[7] He draws the readers’ attention to the facial expression of the prisoner, which bears traces of ecstasy, and according to him there is an argument to be made about the kind of pain that brings pleasure—though the prisoner has taken a dose of opium beforehand.[8] A large crowd gathers around the scene to watch. There is an air of festivity, as is often the case when someone is executed in public. Lingchi differs from other forms of execution in that its unusually long duration brings, or rather, forces the executioner and the executed into a close, or even intimate confrontation. In a way, the former is slowly acquiring a thorough understanding of the latter in terms of his bodily structure, of “what’s happening underneath the skin” ([Plaque with background information about Lucian Freud: New Perspectives exhibition], n.d.)—a focus shared with Freud’s paintings. As he teases away skin, muscles, and sinews, the executioner also presents the executed with radical self-knowledge, which becomes invalid as soon as it is revealed because one can only see one’s flesh clearly when it is peeled off one’s bones. If there is indeed any kind of ecstasy, it might as well be that of knowing oneself, finally, at the point of death. Back then, a lingchi done well was regarded similar to art: it took experience and expertise to prevent the executed from dying too quickly. Such a collective act of cutting and witnessing is equally dependent on the body as any kind of disease: it can only keep happening as long as the body goes on, just as what a disease wants is, paradoxically, that this body never diminish. Yet bit by bit it does disappear, and everyone keeps watching. Freud’s paintings, especially portraits, are lingchi in reverse. Rather than removing them, he places muscles onto a skeleton bit by bit, brush by brush, until the whole figure appears in front of him. Yet such a process only reminds the viewers, once again, of the validity of its reversal, especially because Freud makes no attempt to smooth the brushstrokes: the traces. When we look at the paintings we see the transience of flesh made permanent by paint, while this permanence is nothing more than an illusion, for paint itself is subject to time as is the flesh it depicts. A carefully rendered portrait is an embodiment of the way time may pass through the sitter, as is the body of a prisoner, or that of a patient, slowly and methodically sliced into pieces.

Watching someone die by a thousand cuts, we see right before our eyes a human body being turned, quite literally, inside out. There is the blurring of boundaries between what is taken to be the inside versus the outside, a distinction based on which we as individuals construct the stability of our being. The fragility and ambiguity of such boundaries are something we have to confine to the liminal space, in order to go on living; the process of abjection. But then, naturally, it is followed by a question: at what point does the sight become unbearable? If, as Julia Kristeva suggests, “the corpse is the utmost of abjection and the most sickening of wastes”,[9] and if seeing it places one in a world that has erased its borders, how can we reconcile the fainting sensation she describes in witnessing death infecting life with the fascination, shared among many, in watching a highly violent public execution? “It is thus not lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, order.”[10] Does this indicate that the festivity of public executions originates in the restoration of social order that enables the spectators, once again, to return to their previous life, a life that is imagined to be uninfected by crime? There is, always, the (delusional) belief that the society at large is being cleansed by wiping out the convicted, a beneficial sense of nausea to the literal point of vomiting, a clearing out of filth for the purpose of continuing with life. It even extends into the ambiguous idea of immorality. What a wonder, the spectator exclaims, that the body can approach death ever so closely yet still go on breathing, hanging on to the thread of life stretched impossibly thin. Yet more than that, situating oneself as not there and not dying cut by cut, one is able to rise above death and, for however long the inner experience of watching someone die remains with them, find oneself firmly grounded in the domain of the living. The more violent the death, the stronger the differentiation between one and the Other. In declaring, “I won’t end up like that,” one is also saying, “I will live on and on and on.”

Watching someone gradually succumb to illness does not afford the same illusion, especially when it is a person close to you. Now there is no way for you to expel that which is hauntingly terrifying, for it resides within the sick body in the form of a void, a hollowness. In the symptom, such as a monster, a tumor, a cancer that the listening devices of the unconsciousness does not hear, signs of decay permeate the person, so that to cast these signs aside means to do the same to the person, a choice out of the question. Instead, we must confront them, which is to say, it, and this confrontation serves as a reminder that such hollowness lies in your body as well. It pulls you back onto your own corporeality as a temporal being, a notion that is often repressed in the name of its deeply threatening horror. It came as no surprise that, when my grandfather kept complaining about an insatiable hunger that led him to eating almost continuously throughout the day, I felt this horror in its most intense form. It was the kind of hunger that pointed to that very hollowness, signifying a body that was slowly falling beyond the limit of the border that marked one’s condition of living being, simultaneously consuming food and being consumed by illness. Yet the more he consumed, the more he diminished. It was as if what we were witnessing was unstoppable self-consumption, a blurring of the division between the consuming and the consumed, that constitutes the most archaic experience of abjection.[11]

It sometimes happens that, while looking at Freud’s paintings, I get the feeling that what’s before my eyes is something I ought not to see, as is the photograph of lingchi, or my grandfather’s bearing of his own body, demanding our attention and care. To confront them is to witness a forbidden subject, something taboo, having it laid bare out in the open. Precisely because they serve as a reminder of the inherent instability of those boundaries between the inside and the outside, underneath them we find, again, the shadow of a specific kind of chaos that is both a pre-condition and aftermath of desire. Such desire is not necessarily—and in Freud’s paintings, never—directly sexual, but we could still examine sex as its most radical parallel. In Geoffrey Gorer’s essay “The Pornography of Death”, there is a linking of pornography and death on the basis of both as subjects of taboo.[12] He argues that, by eliminating death from daily conversations just as how talks of sex were once strictly restrained, we establish the basis for death to be depicted in a sexualized manner, in literature as well as other forms;[13] the less we talk about death, the more likely it will be turned into some spectacle (think of lingchi and Bataille’s description of the photograph). Yet maybe sex and death do function in the same way, not merely in terms of being a rupture, as Ariés quoting Sade in Western Attitudes Towards Death.[14] They seem to follow a similar arc, too, namely the slow withdrawal of definitive purposes from the body. In sex, too, one feels oneself as energy, and in many cases its messy overflow ends in orgasm, la petite mort, which in its most cruel form is likened to death because it is a reminder of how closely the whole sexual encounter mimics dying, as the self dissolves temporarily and thus approaches transcendence. Such an experience mirrors death directly, not as a metaphor. There is nothing symbolic in sexual pleasure and illness and death. Illness desires a body just as a body desires another body: it wants to become one with its subject, to belong to it and simultaneously claim ownership of it, to see and be seen physically, to smell, touch, taste and be smelled, touched, tasted carnally. This horror, of sensing, or merely witnessing, the highly organized system of a human body being returned to energy with no fixed direction of flow, meaning no purpose, manifests in the confrontation with the sick body. It appears to be the consequence of a desire that goes wrong, and we all know the kind of desire so intense it makes us sick. Every time we open our eyes and find ourselves still intact, it feels like a narrow escape. This knowing fear thus provides the basis for countless works of art. They lay bare something we are all aware of yet often refuse to consider in too much detail, namely that one day our physical being will end. In desiring to capture the truth in our transient corporeality, Freud’s portraits, among other artworks, simultaneously reveal the brutality and futility of desire in all its forms.

For me, the most striking drawing by Freud will always be his sketch of his mother, done immediately after her death.[15] Yet it is not the face of the deceased, placed right in the centre of the sketch paper, that makes the drawing so striking. Such a face is almost foretold by a series of paintings Freud made, over the years, of his mother resting. [1] As the woman in the paintings gradually ages, her face seems to be saying more and more about its own final rest; it is a face already shadowed by death, as is nearly every face of a motionless person. What’s striking about this hasty sketch is its immediacy, its spatial and temporal closeness to the event—or, rather, the aftermath of an event—it is depicting. Looking at the drawing, it is difficult not to ask, why? Why did Freud draw his mother, when she had already died? Why would anyone do it, for that matter? The question has little to do with morality, for it is really asking, how could anyone bear such a task, sitting face to face with a beloved one who has only just passed away, without breaking down under the weight of sorrow and that strange numbness? Yet in this case, strangely, the act of drawing could also function in the same way as the turning of one’s head and the averting of one’s eyes; the sketch paper becomes a veil, hanging between the dead and the living. To narrate, visually, the death of someone so close to you, one starts in the same space with the deceased, i.e. behind the veil, and throughout the process one can’t help placing oneself in front of the veil and thus separated, detached from what’s behind it.

In discussing photography (and other forms of art) that depicts suffering and pain, Sontag does not intend her analysis of to be applied to images like The Painter’s Mother, Dead, either. Indeed, shown in this sketch is the kind of individual death our society often deems fortunate, just like my grandfather’s. Yet it is still terrible to look at. Death, regardless of the cause, is extreme to the person in whom it takes place, and the loss is extreme, absolute, to those still alive. There could very well be the shame of failing to prevent it, a failure that is the basic living condition of all temporal beings. And then there is violence. With painstaking honesty Freud documents the formal starting point of elegiac mourning, whose very principle, according to Froula, is the necessity of relinquishing the dead and of forming new attachments in order to carry on with life.[16] With the use of a word like “relinquish”, the living’s surviving the dead is depicted as a violent act. Such survival, being a necessary condition of any kind of documenting at all, thus lends the latter a certain quality of violence as well.

This understanding of what it means to live on, shared by the painter and the viewer, is what makes the small sketch so hard to look at, yet so relevant at the same time. It shows, in all openness and honesty, the painter negotiating his way through the death of his mother. In fact, such negotiation happens even earlier, with his series of her resting. To borrow Barthes’ words, in Freud’s paintings we see the punctum that is “no longer of form but of intensity, for it is Time, the lacerating emphasis of the noeme (‘that-has-been’), its pure representation”.[17] They are “saturated by the passage of time”,[18] by what has been, to the point that they strike the viewers as testimonies of that severance of time passed from the physical body that has experienced it from within. Confronted with their portrait, a sitter sees an individual that is simultaneously who they are (For he “portrays not only their appearance, but the essence of their character.”[19]) and now dead, survived by the person that lives on in the present time. Freud’s work has nothing to do with transcendence of the human body achieved through technology, an idea that’s foundational to posthumanism, yet it opens up an aesthetic space that accommodates a very particular form of posthumanist self-mourning, of realizing the fantasy of surviving one’s death.[20] Here death is embodied in a pose stretched into near eternity, and survival in the act of setting one’s eyes on oneself in that eternity, for a fleeting second, and walking past it, still in one’s living flesh. Thus Freud’s paintings of his mother, his mother as the sitter for his work, together with himself, enter a complicated relationship in the form of looking and being looked at, for it is always, to some degree, a mutual act. In this sense then, it is not only the painter’s negotiation but, partially, his mother’s as well. Living with the precondition that “we are all mortal” and death is bound to be a “horrible surprise”,[21] in the end it is up to each one of us to find our own way to deal with it. We put our effort into this seemingly impossible task, and texts, paintings, sketches, as well as photographs, if nothing else, at least testify to such an effort.

According to the wall text that accompanies the drawing of his dead mother, Freud has to ask the nurse to wait and let him draw the deceased before covering the body ([[Plaque with background information about The Painter’s Mother, Dead], n.d.]). One might say that the unfolding of that sheet of sketch paper is the first manifestation of his grief (which is not to say that grief has not been there prior to this point). In a way, his gesture is a more direct embodiment of grief than a text like A Very Easy Death, not only because in his case death has already visited. Death, as an occurrence whose beginning and end are equally unknowable, effects indescribable, provides for its witness a confrontation that can’t be easily put into words, if they feel able to talk about it at all. It is a slow silencing of the dying body as well as the body that sees and waits. It keeps happening until it happens, and the moment it happens it ends. Death catches itself and destroys itself, like a chemical reaction, and it is always nearly impossible to reconstruct that moment with language. What Freud accomplishes serves to translate the unspeakable into a language he is used to reading and speaking, and with it the crucial moment might just turn into something he can better understand. The language is not so much drawing as the gesture his body makes while doing so, the way his hand holds the pencil and moves across the blank paper. It sees the corporeal being translated in an equally corporeal way. With that bedside sketch, the still figure is transformed into a very specific gesture that, as long as it is carried out correctly, is capable of reconstructing the image of the painter’s dead mother over and over again. It is somewhat comparable to repeating the words, “the moment my mother died”, or holding onto a photograph of the dead and looking at it from time to time, but also completely different because the translated “text” is embedded in the painter’s body, inseparable from the body and inaccessible to anyone else. It is a special means of translation and preservation arguably only a painter might achieve.

Whatever the medium used, to document trauma and sufferings, of which illness and ageing are just one example, might always come close to translation. In his essay “The Translator’s Task”, Walter Benjamin suggests that “the ultimate purpose of translation is the expression of the most intimate relationships among languages”,[22] within the context of constant transformation and renewal of both the original and the translation itself. Though the essay is predominantly concerned with the way in which different modes of intention found in different languages may become recognizable as fragments of a “greater language”, it ends up providing a most fitting description of the act of documenting the unspeakable: death, and the decay that leads up to it. They are comparable to original texts with a specific significance, and in terms of things like the death of an ageing person, this significance may seem to concern their family members alone. Yet the experience is also universal, meaning that it has an inherent translatability. Theoretically, what we have gone through should be able to be expressed through words: it is an concrete event with a beginning, middle, and end, a narrative embedded in linear time. In practice, however, there remains in it, as “in all language and its constructions, something incommunicable”.[23] This something is what dictates that, in order to represent illness and death, sometimes one has no choice but to shift the focus onto documentable incidents directly adjacent to them. In this process of selecting and representing there emerges a kind of fiction, a translation that now sets the original into a new language.

It is probably here that a translation remains the most obviously “inappropriate, violent, and alien with respect to its content”,[24] for there is no place else where it seems so clear that “the connection between the translation and the original has no significance for the original itself”.[25] Does it matter to the ill, to the dying, that someone is writing down everything surrounding their dying, weaving an account that even the survivors might not find of much interest? Does it matter to Freud’s demented mother that her once beloved son is now painting her portraits, precisely because she has stopped paying attention to him? But also, does it matter that, according to Freud’s claim, the painting sessions often improved her mental state?[26] Grant that it does matter, to whom, then? And in what ways? To translate, Benjamin believes, is to set free, in one’s own language, the pure language spellbound in the foreign language, and thus coming to terms with the foreignness of languages to each other.[27] There is, of course, nothing that could be named as pure being, or pure experience, which is spellbound in sudden, disastrous events that have come to encompass the entirety of ordinary daily life; what is being liberated by language, if anything, is the language itself. It rescues itself from the threat of a terrible occurrence that seems utterly foreign to its previous usage, proving its elasticity by finding ways to name, narrate, and translate.

* * *

One last time, that hospital room, where Freud sits face to face with his dead mother. Think of that sheet of sketch paper and its presence. How does it get there? I mean, when a painter knows that his mother is dying, does the paper and pencil he always carries with him suddenly acquire new weight, since he is aware that any moment now he might need to pull them out in order to draw his mother, dead? Or actually, he asks for and receives a scrap of paper and a pencil from the nurse, maybe? But that is not what I mean to say. I mean, think of the journey, when death is not so imminent yet, between where the painter lives and where his mother lies, breathing: the journey between the domain of the living and that of, not yet the dead, but the in-between, the transforming, a journey to be made until the dying can’t afford waiting anymore. Think of the necessity of journeying, the act of journeying as something that keeps unfamiliar transformations—illness, and later, maybe, death—outside the realm of the familiar, the domestic. Such transformations aren’t allowed at home. Only animals transform at home, if they have one to begin with.

Freud also paints dead animals. In particular, there’s the famous Dead Heron.[28] Walk up close to this painting and you will be amazed: what cruelty in painting the dead bird’s beak so precisely, in so bright a yellow, the edge of its shape so sharp and clear, unquivering in the face of death. Compared with The Painter’s Mother, Dead, there is hardly anything dead, or anything commonly associated with death, about this heron: no blank facial expression, of course; no wound; no blood. It lies motionless on the table with its wings spread. But who is to say that it is not merely anesthetized? The same goes for his other paintings of dead animals, of a monkey on a plate and a chicken on a table: these paintings have in them a serene quality that makes it seem palpable that their subjects are only in repose, rendering such a death almost non-threatening, safe to keep, for a time, within a domestic space. A similar thought may not come to mind when one encounters The Painter’s Mother, Dead. We recognize death in this face. How can we begin to understand, to believe in some other species’s death, one that is so foreign to us, assuming such a different appearance? Or is it really foreign? Or, can there ever be a manifestation of death, any death, that makes it familiar?

Freud is not interested in visual illusion, nor hyperrealism. If you lift your finger to a portrait, there is no doubt that it would land on nothing but paint, layers and layers of it. In his portraits, especially those finished in the later stage, the way he paints is comparable to how a sculptor moulds a figure. It is crucial for him that a painting retain the materiality of paint. But if this is the case, then we are not dealing directly with the materiality of human muscles, or, in his own words, “what’s happening underneath the skin” ([Plaque with background information about Lucian Freud: New Perspectives exhibition], n.d.). We see, instead, its affect, as narrated by paint. Through his pursuit of truth, Freud arrives at a more and more accurate form of fiction that conveys the affect of a specific subject’s being there, assuming a specific posture, being in their specific mental state. In the end it is only the narrative constructed from paint—and how it impacts the viewer—that truly matters. In its turn, the actual body of the subject becomes nearly dissected. Ultimately, his are the kind of portraits that, once come into view, forever deprive the viewers of a innocent vision that allows them to see any body as an integral whole. The act of piling and shaping and reshaping his paint results in a painfully clear reminder of the whole as always a sum of smaller parts that can be ruthlessly undone (on canvas, and elsewhere). We see this in his unfinished portrait of Francis Bacon.[29] The tone is not evened out, and the muscle structure is so thoroughly depicted by both color and texture that it seems as though the face had been flayed. What the painting shows is precisely that there is no continuous truth waiting to be revealed, but fragmented parts always bordering on, if not already falling into, some form of chaos. Such a working method, then, also becomes an embodiment of the painter’s attitude towards death. It could happen to anyone, at any time. You can’t avoid it, but you may prepare for it, by leaving what you are working on as presentable as possible, like Freud did every day in case he died that night.[30] It is in the same sense that while working with a sitter, the painter always starts from some sort of presence and, ultimately, addresses potential absence. When the human figures are gone, the space remains, and with it, time. A painting is also a documentation of these two. Though he never posed his models, Freud did use tape to mark out the position of every object in a setting, “as if it’s a crime scene”.[31] The space is given equal importance as the body situated within it.

And now, take Bella and Esther,[32] a double portrait of Freud’s two daughters. Here they lie side by side on the leather sofa, their bodies relaxed, heads turned casually towards the painter/viewer. Yet when I see the painting I can’t look away from their faces, carefully rendered by so many brushstrokes that the skin appears to be covered with blisters. I can’t help staring, because the wall text says that Freud values the time he spends, as a painter, with his family members, as his sitters, and that those in his family enjoy it too, and offered as some sort of proof there is Naked Child Laughing[33] hung close to this double portrait, a painting that shows Annie, his oldest daughter, naked and laughing, her head bowed and eyes downcast. She seems no less relaxed than Bella and Esther. The brushwork of this painting, however, is less refined, which lends the unclothed flesh a rhythm that approaches the motion of water. Annie sits still, but there is movement within this stillness, and because of such underlying movement this painting differs fundamentally from that of Bella and Esther. In the latter there is an almost unusual quietness, a sense of submission as the consequence of both subjects lying supine and the perspective the painter chooses—Freud is standing over them and looking down. They are also wearing clothes of solemn colors: black, indigo, white. They are not laughing or even smiling. They are truly still, truly silent. What about the sitters is the painting trying to preserve, to tell? Looking at them, it is hard not to wonder what exactly is happening when, with the uttermost tenderness and loving care, a painter spends hours and hours painting faces that, once finished, appear desolate, savaged even, faces of his daughters that call to mind faces of death. It is like an overflow of time the skin fails to contain. By means of tenderness we arrive at a manifestation that resembles a form of brutality. I say this about the painting, but of course I am also thinking of A Very Easy Death and all the other texts I have read during our familial turmoil, of our attempts as humans to look at time and loss in the face and to create something, anything, as a counteractive measure, including this piece.

Notes

1. See, for example: Freud, L. (1982-1984). The Painter’s Mother [Oil on canvas], and Freud, L. (1975-1976). The Painter’s Mother Resting I [Oil on canvas].

Bibliography

Ariès, Philippe. Western Attitudes Toward Death: From the Middle Age to the Present. Translated by Patricia M. Ranum. Marion Books, 1976.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. Hill and Wang, 1981.

Bataille, George. The Tears of Eros. translated by Peter Connor. City Lights Publishers, 1989.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Translator’s Task.” Translated by Steven Rendall. TTR 10, no. 2 (1997): 151-65. https://doi.org/10.7202/037302ar.

Borg, Ruben. Fantasies of Self-Mourning: Modernism, the Posthuman and the Finite. Brill Rodopi, 2019.

De Beauvoir, Simone. A Very Easy Death. Translated by Patrick O’Brian. Pantheon Books, 1985.

Finger, Brad. Freud: Masters of Art. Prestel, 2020.

Freud, Lucian. Bella and Esther, 1988. Oil on canvas, 73.7/88 cm. London, The National Gallery, London.

Freud, Lucian. Dead Heron, 1945. Oil on canvas, 50.8/76.2 cm. London, The National Gallery, London.

Freud, Lucian. Francis Bacon, 1956-57. Oil and charcoal on canvas, 35.5/35.5 cm. London, The National Gallery, London.

Freud, Lucian. Naked Child Laughing, 1963. Oil on canvas, 34/28 cm. London, The National Gallery, London.

Freud, Lucian. The Painter’s Mother, Dead, 1989. Graphite, 33.3/24.4 cm. London, The National Gallery, London.

Froula, Christine. “Mrs. Dalloway’s Postwar Elegy: Women, War, and the Art of Mourning.” Modernism/modernity 9, no. 1 (2002): 125-63. https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2002.0007.

Galenson, David W., and Simone Lenzu. “Two old masters and a young genius: the creativity of Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, and Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Journal of Cultural Economics 47 (2023): 489-511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-023-09476-9.

Gorer, Geoffrey. “The Pornography of Death.” Encounter 5, no. 4 (1955): 49-52.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Columbia University Press, 1982.

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. Picador, 2003.

Wolff-Bernstein, Jeanne. “Between the Artist’s Studio and the Psycho-Analytic Office: A Comparison of Lucian and Sigmund Freud’s Interior Spaces.” In Private Utopia: Cultural Setting of the Interior in the 19th and 20th Century, edited by August Sarnitz and Inge Scholz-Strasser. De Gruyter, 2015.

[1] Simone De Beauvoir, A Very Easy Death, trans. Patrick O’Brian (Pantheon Books, 1985), 112.

[2] Beauvoir, A Very Easy Death, 110.

[3] Beauvoir, A Very Easy Death, 111.

[4] Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (Picador, 2003), 34.

[5] Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 33.

[6] Jeanne Wolff-Bernstein, “Between the Artist’s Studio and the Psycho-Analytic Office: A Comparison of Lucian and Sigmund Freud’s Interior Spaces”, in Private Utopia: Cultural Setting of the Interior in the 19th and 20th Century, ed. August Sarnitz and Inge Scholz-Strasser (De Gruyter, 2015), 37.

[7] George Bataille, The Tears of Eros, trans. Peter Connor (City Lights Publishers, 1989), 205-207.

[8] Bataille, The Tears of Eros, 207.

[9] Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (Columbia University Press, 1982), 3.

[10] Kristeva, Powers of Horror, 4.

[11] Kristeva, Powers of Horror, 7.

[12] Geoffrey Gorer, “The Pornography of Death”, Encounter 5, no. 4 (1955): 49.

[13] Gorer, “Pornography of Death,” 52.

[14] Philippe Ariès,Ariès, Philippe, Western Attitudes Toward Death: From the Middle Age to the Present, trans. Patricia M. Ranum (Marion Boyars, 1976), 57.

[15] Lucian Freud, The Painter’s Mother, Dead, 1989, graphite, 33.3/24.4 cm, London, The National Gallery, London.

[16] Christine Froula, “Mrs. Dalloway’s Postwar Elegy: Women, War, and the Art of Mourning”, Modernism/modernity 9, no 1 (2002): 129, https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2002.0007.

[17] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (Hill and Wang, 1981), 96.

[18] Wolff-Bernstein, “Between the Artist’s Studio and the Psycho-Analytic Office”, 38.

[19] David W. Galenson and Simone Lenzu, “Two old masters and a young genius: the creativity of Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, and Jean-Michel Basquiat”, Journal of Cultural Economics 47 (2023): 498, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-023-09476-9.

[20] Ruben Borg, Fantasies of Self-Mourning: Modernism, the Posthuman and the Finite (Brill Rodopi, 2019), 12.

[21] Beauvoir, A Very Easy Death, 111.

[22] Walter Benjamin, “The Translator’s Task”, trans. Steven Rendall, TTR 10, no 2 (1997): 154-56, https://doi.org/10.7202/037302ar.

[23] Benjamin, “Translator’s Task”, 162.

[24] Benjamin, “Translator’s Task”, 158.

[25] Benjamin, “Translator’s Task”, 153.

[26] Brad Finger, Freud: Masters of Art (Prestel, 2020), 66.

[27] Benjamin, “Translator’s Task”, 157.

[28] Lucian Freud, Dead Heron, 1945, oil on canvas, 50.8/76.2 cm, London, The National Gallery, London.

[29] Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, 1956-57, oil and charcoal on canvas, 35.5/35.5 cm, London, The National Gallery, London.

[30] Miguel Angel Gonzalez-Torres and Aranzazu Fernandez-Rivas, “Lucian Freud: the ruthless genius”, International Forum of Psychoanalysis 30, no. 2 (2021): 106, https://doi.org/10.1080/0803706X.2020.1831064.

[31] Wolff-Bernstein, “Between the Artist’s Studio and the Psycho-Analytic Office”, 38.

[32] Lucian Freud, Bella and Esther, 1988, oil on canvas, 73.7/88 cm, London, The National Gallery, London.

[33] Lucian Freud, Naked Child Laughing, 1963, oil on canvas, 34/28 cm, London, The National Gallery, London.