It was early when we arrived at the dairy, and according to what he told us then, as he looked around, nothing had changed. I was skeptical. In fifty years, nothing had changed?

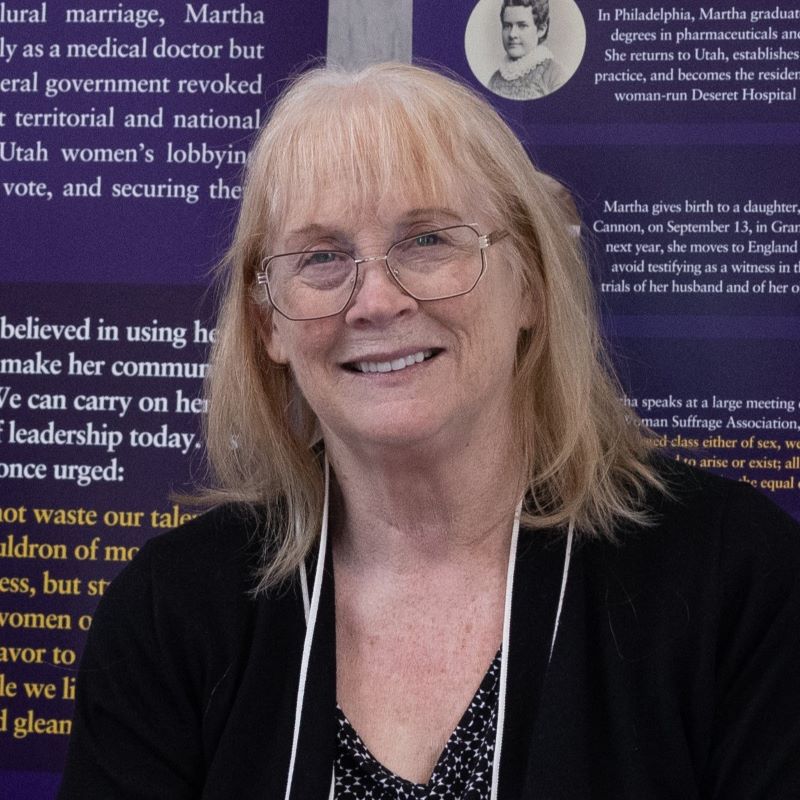

We – my friend, Horst, his wife, Mirjam, friends Harold and Marian Kunath, and I – were standing in the courtyard of a dairy, a few miles outside the town of Jawor, Poland, a small town about 70 kilometers west of Wrocław. Its population was 21,000 – little changed from 1945, the year Horst had last seen his home, just before all Germans were forced out of the town he had known as Jauer, Germany.

All the buildings stood just as he remembered, except, he noted, they had new windows and a fresh coat of stucco. The battle trenches, dug as Soviet troops marched through on 12 February 1945, had been filled in. Horst was almost too enthusiastic, causing me to wonder what memories had been awakened by being there again. If nostalgia really is history’s lie,1 I wondered how many of his memories reflected facts and how many were merely how he wished it had been.

It was still a working dairy, and we were welcomed by the manager, who, luckily, spoke German. He took us around the grounds, pointing out the manager’s house, the storage sheds, and the house Horst’s family had occupied. Of course others, Poles not Germans, lived there in 1993. I kept turning in a circle, trying to take it all in, comparing the reality to the sketches I had made from his descriptions.

Then I abruptly left the others. I was always uneasy in a group and felt so clumsy about fitting in with the conversation and laughter. Sometimes it was just easier to be alone and steal a moment to reflect. I walked out through the gate to the road connecting the dairy to Jawor and to the small village of Paszowice (formerly Poischwitz) and just looked. To the right and to the left, the road was long and all I could really see were the fields, their expanse only interrupted by a few linden trees.

My mind wandered back in time. In one direction, in happier days, three children flew towards Jauer on their way to school. From the other, an over-weary mother, hoping to find her husband there, with her exhausted children arrived in May 1945 to a place that hardly resembled the home they had left only months before.

Tears began to fall. I could not help it. Crying has always been my fallback response to events. I cry if I am tired, if I am angry, if I am sad. Even, sometimes if I am happy. And on that day, I could not erase the image of that brave woman, of those courageous children. I tried to imagine their journey and wondered if I might have succeeded at a similar task. Probably I, too, would have found hidden reserves, just as she did, to keep my own children safe.

I was so lost in thought that I did not hear someone come up behind me. It was Horst. He tapped me on the shoulder. “We are going to tour the dairy now. Willst du auch mitkommen? Do you also want to come?” I turned my head away so he would not see my tears. “Ja, ja, einen Augenblick. Just a minute,” and I motioned for him to go on ahead.

I had been interviewing Horst and writing down his wartime story for the past year. We both lived in Worblaufen, Switzerland, with our families and had become good friends. He often teased me about the notebooks I used. They were small and thin, just the same as the ones children in the primary school used. One of mine – and he laughed when he noticed it – actually had belonged to one of my children. It still had Schreiben (“penmanship”) written in an unformed hand on the cover.

As World War II in Europe was ending, Horst and his family were continually on the search for home; in other words, for a safe place where they could be together and where the bombs were not falling. They left Jauer to go to relatives in western Germany, but the bombs found them there. So they left that home and travelled nearly 700 kilometers on foot and by train to reach Jauer once more. All the world was fleeing eastern Europe in front of the advance of the Soviet army, but this inexperienced mother with her young children, was walking straight into their arms.

Such is the pull of home, of Heimat, of a place familiar to generations of family members, where the sounds of language were as expected, where the weather was as expected, where the light filtering through the trees in advance of a storm was as expected. Nothing was feared because everything was, yes, as expected. Variety is not what is wished for when one thinks of home; familiarity is.

I attached myself to the back of the group just as they entered the dairy. The last time Horst was there, the conveyor belts were broken and looked like they had been thrown about the room. And quark (a yoghurt-like product), quivering with maggots, was on the windowsills, inedible, even for a hungry little boy. Now, the conveyor belts were in order, but everything still looked like no more than a tangle of hoses, faucets, and meters; all in a run-down condition. Steps led up to a gallery under a row of rectangular windows just under the ceiling where vats and kettles were stored.

The next thing I noticed was the awful smell. There was easily a quarter inch of milk all over the floor, dripping from a broken faucet. We had no choice but to wade through it. I put my feet down gingerly and tried to resist holding my nose. The conveyor belts took wheels of cheese from one room to another, at intervals having mysterious things done to them until, in the final room, they were resting on wooden shelves, ready to be sold. The manager was pleased to give us tastes of the various cheeses and offered us whole ones if we wanted to buy. I am sorry to admit that I could not bring myself even to taste the cheese: the smell was so bad. Fortunately, the others were more gracious than I and not only tasted, but bought.

We next headed to Paszowice, where Horst’s family had made a second, secret home-in-hiding for the last months they remained in the area in 1945. Paszowice was as forsaken in 1993 as it had been then: a cluster of decrepit farmhouses. The population was not quite 4,000. Horst knocked on the door of the then-abandoned farmhouse they had hidden in. The young man who answered the door made it clear that we needed to leave: immediately! Even speaking no Polish, we could understand: “Get out and leave me alone.” He would not even let us take a photo. Well, it was his home now and the memory of Germany and Germans was still strong and unwelcome. He slammed the door in our faces.

We entered a small restaurant – or bar? I do not remember, but “small” was the operative word. It was dark and crowded with people sitting at wooden tables that were scarred and pitted and surrounded by rickety chairs. We were immediately the center of attention. Probably not very many strangers pass through Paszowice.

“Strangers?” I imagine Horst responding. “How can I be a stranger in my own home?”

We nursed small glasses of Coke and tried to converse with the other patrons, who were very interested in what we were doing there. They were curious and a bit fearful. Germans were still regarded with suspicion. Why so many years after war’s end? Until it was clear that the post-war borders of Poland would not change, and that Germans expelled from their former homes would not be allowed to re-claim their property, Poles recognized that they were living in homes that might technically still belong to German families.2 That young man who would have nothing to do with us was likely afraid that Horst had returned to stake a claim to his family’s former property. Once we made it clear that we were Swiss, everyone relaxed. Strictly speaking, only Mirjam and I were Swiss citizens; Horst and the others were German. Still, in Paszowice we could only benefit by allowing the misconception to stand.

Finally, we went into Jawor.

We looked at the well-known protestant church, Friedenskirche zum Heiligen Geist, built in 1655, and Horst’s old school, three stories high, now boarded up after several fires. The Rathaus, city hall, built in 1895, was still standing in the middle of the town. Horst recognized the buildings with their arcades still sheltering the sidewalks in the main part of town. Under the arcades, the shops appeared abandoned, and it probably looked little different than it did when Horst’s family returned in May of 1945.

Is this the same place, really, where Horst and his family had lived? Geographically considered, it is, of course. We met a man there who was reluctant still after nearly fifty years to admit he was German. But word of the German-speaking strangers who had arrived had spread throughout the town, and he sent his grandson to fetch us. He was happy to speak German again, because he had stayed with his wife, a Polish girl, when the Germans were driven out of western Poland. To remain, he had to change his name to a similar, but Polish one, and never speak German again or even keep things written in German, such as books or christening certificates or the like. The police would listen at the windows to hear if German was being spoken and perform unannounced searches for forbidden German items. Mail directed to former German addresses was returned: “locality unknown.”

Our new friend had seen German place names overwritten with Polish place names; his own language supplanted by Polish. Did he have thoughts at all anymore? A rhetorical question, but if the German language was forbidden, then German thoughts must of necessity die stillborn. Where did he find himself, really? And where were we on that summer afternoon? We were in a place where German footprints had been nearly obliterated by Soviet soldiers, where Soviet tracks were replaced with Polish. A palimpsest of memory and history. Who, today, could call this place home? In 1945, as Germans were leaving, and as Polish refugees were arriving, it was not uncommon for a German family and a Polish family to live together for a short while. A curious combination of two languages, two nationalities, two traditions – ostensibly enemies – living side-by-side in one apartment. But in 1993? The Poles who had fled Ukraine and had come to Jawor to live in the deserted towns and villages did not yet feel at home in 1993. Nor did Horst, who had become a foreigner, an interloper in what had been home but was now a foreign country.

Horst initial impression was pure nostalgia for something he longed for but would never be his again. In fifty years, everything had changed.

But nostalgia does not have to be a lie – it is what drives us to discover new homes, to become part of a new community, to forge new traditions and make new friends. Nostalgia – the dream of what has been – urges us on, like Horst in the aftermath of World War II, or like any of us who take a job in a new city, in another country. That dream, the memory of what may never have been, but then again, may have been, just so, gives us the courage to create a home – a Heimat, tradition, a sense of belonging and safety – anywhere we land.

The Hasidic authority, Ba’al Shem Tov said, “Forgetting lengthens the period of exile. In remembrance lies the secret of deliverance.”3

“Where is my home?” Horst asks. “How can I return to a time and place that no longer exist?” He went to Jawor, Poland, seeking Jauer, Germany. Everything had changed, but once there, as memories flooded his mind, and he remembered what had been, he was there, in the place that had been erased from the map, but could never be erased from his memory. Home. Heimat. Identity. That does not disappear.

- Many have expressed this idea. One example in R. A. Salvatore in Streams of Silver: “Nostalgia is possibly the greatest of the lies we all tell ourselves.”

- The question was essentially settled when the German Chancellor, Gerhard Schröder bowed on the steps of the memorial to the Warsaw Uprising on 31 July 2000 and assured Poles that the German government would oppose any claims from former German residents of what had been Germany, but was then, Poland.

- Rosenberg, David, ed., Testimony. Contemporary Writers Make the Holocaust Personal, New York: Random House Time Books, 1989.