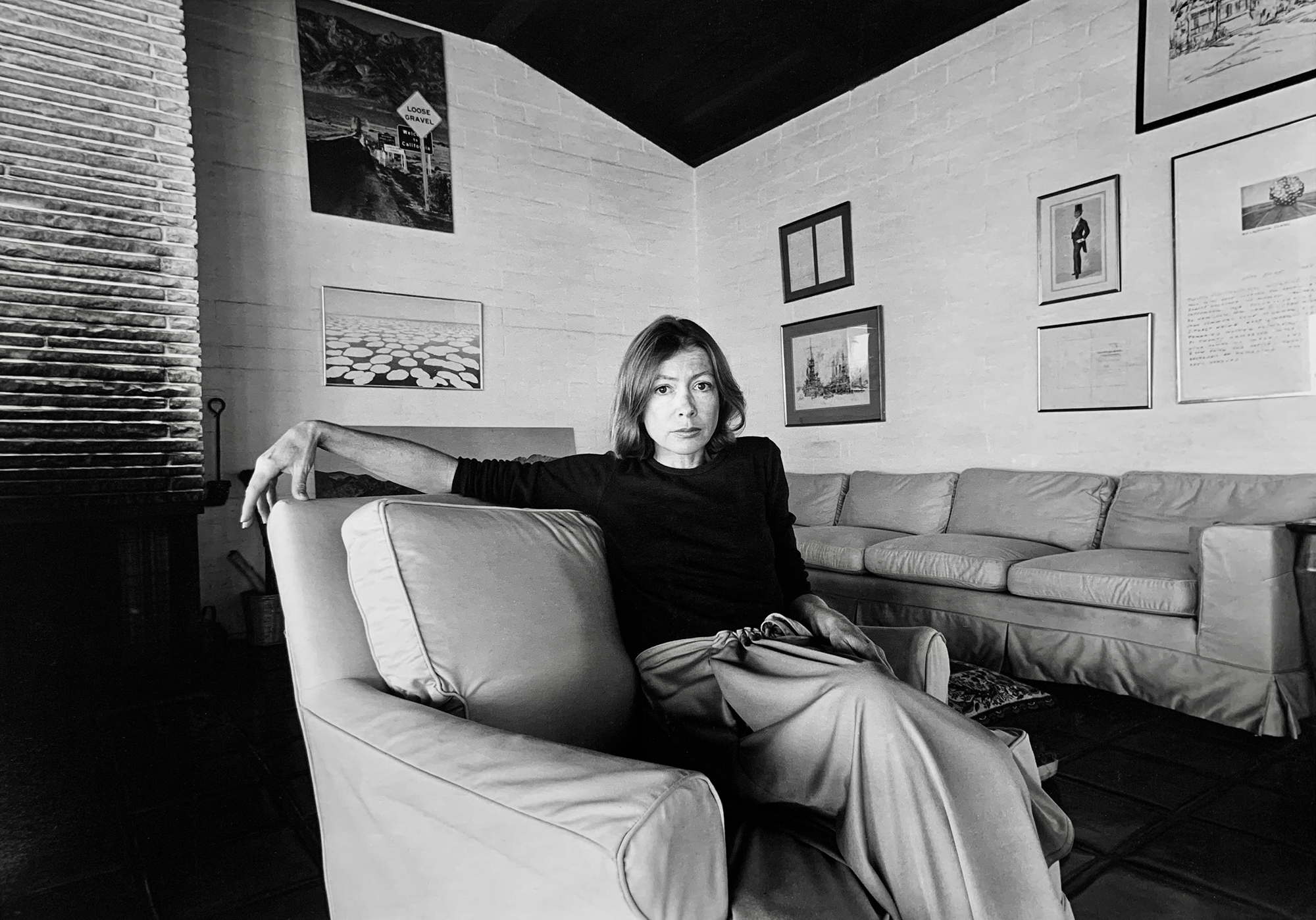

Cover art

Original by Martin Saint

We departed Yokohama Station after lunch, a spree of vermouthy aperitifs blunting our wits, only to find ourselves besieged by gale-force rain sheeting down from the east. It was my fifth and final trip to the mountain that year, May, 1923, after which I’d be heading back to the University of Chicago to finish out my sabbatical. The plan was a three-headed hydra: Head 1—collect volcanic rock samples for a geologist acquaintance of ours in Tokio; Head 2—beef up the notations I’d made on the Hoizen cone during my previous trip for a book I was writing on the mountain; and Head 3—allow for yet a final opportunity to witness Fujiyama’s famed sunrise from its summit, the Cloud Sea, since all of my previous attempts had been ambushed by hostile nimbostrati clouds. This, J. K. Wonzniak’s fifth year in the throes of an opium addiction whose narcotic voodoo had kept my snookered knee in steady cheer ever since my accident. It goes without saying, I’d taken measures to ensure ample stocks of tincture for the trip.

My two companions were the folklorist Yanagita Kunio and Marbashi Juichiro, a crackerjack ethnographer who laid claim to having made Fujiyama’s ascent over sixty times. The train cored its way through the mountains, slashing past laurel forests and the limestone coastline. Yanagita was flush to the gills with a spluttering head cold. With each tunnel we hit he pried open the window, dredged the murky wetlands of his lungs with an ungodly erraack!, and offered the debris to the tunnel winds. After one such purging, I said in Japanese, “You ought to have stayed home.”

Yanagita adjusted his straw boater hat to underpin a stray hair and said in English: “On the contrary, Woz. My presence on the mountain is a matter of life and death.”

“Eh?” Marbashi said, edging out of his seat.

“How so,” I said, this time in English.

“I’ve something planned for the sunrise. You’ll see.”

He then opened the window and spat into the wind. Marbashi and I peppered him with questions but ultimately failed in convincing him to unleash the proverbial cat from its bag.

The remainder of our passage to Fujiyama was uneventful except for a brief encounter I had with two female missionaries, fellow Americans. I’d been trotting up and down the length of the car working circulation into the lemon knee when I ran into them. One looked in her sixties. The other was younger, maybe thirty, and was pale and gaunt, a contrast to her dark hair. They said they were stationed in Yokohama and that they, too, were on their way to climb Fujiyama.

“Your first time?” I asked.

“No, no,” the older one said, and told me they’d both hiked the mountain several times.

“Impressive!”

The younger one looked at me with a flat stare.

“I’m gravely ill,” she said. “This will be my final trip up the mountain.”

I don’t recall exactly how I responded, something along the lines of: “Oh dear, sorry to hear that.” I wished them well and returned to my seat. A strange coincidence, I thought. Yangita states that his presence on the mountain is a matter of life and death, and minutes later I meet a woman who’s implied she’s dying. Life and death, indeed.

We arrived near Fujiyama in a town called Gotemba and secured lodging for the evening at a favorite inn of mine, the Subarashi. Scalding bowls of miso soup and cups of Suntory whiskey warmed the chitterlings and lubed the cockles. My knee began thumping out its usual bassline of pain, so I took an extra slug of the old brown and sweet. My injury was the result of a battle royale with the wheels of a grain truck four years earlier. I’d been minding my own business on the corner of Chicago’s Slate and Madison, rabbit-fur trilby in hand, only to wind up getting cold-cocked by said truck tra-la-la-ing down the street. Several surgeries later, my doctor described the remaining sludge that had once been my knee as “bone chowder.” He ended up fattening me with morphine so regularly that after my release, good patient that I was, I continued the habit via opium’s first cousin, laudanum tincture.

Yanagita retired to his futon early, serenading us with percussion blasts of hacking and coughing. Marbashi and I cracked roasted chestnuts over a brazier and waited for a fourth companion to arrive, Marbashi’s friend Sogabe, a geology student from Tokio Imperial. Sogabe was late, so Marbashi and I eventually retired to our respective futons. I couldn’t sleep and fell prey to an opium hallucination of harpies: ugly hags with the bodies of tiny birds, dive-bombing my pajama sleeves. “She devils!” I spat, swatting at them as they stroked my face with their craggy nails, their hot breath whistling in my ears. They eventually flew off, and a gloom descended upon me. The aftermath of an opium hallucination never failed to leave me hollowed and empty, agonized about my station in life. A dark strum of chordwork, this. Buried under the covers, alone in bed—alone in life, by all accounts—I was reminded that I was nothing more than one of those lonely junkies caricatured in the pulp magazines. I thought of the missionary woman I’d met on the train earlier. Was I, too, considered “ill”? How much longer could I go on like this? I’d been toying with the notion of attending an addiction clinic but kept telling myself that my addiction wasn’t really a problem, or that I’d beat it on my own when I was ready. I knew this was a lie.

The truth? Simply put, I was a coward.

A rummy morning declared itself with the squeaks of hawfinches outside the window. The dawn revealed two new particulars that had manifested overnight: a rain-drenched Sogabe, asleep on a futon beside Marbashi, and a spluttering hack of my own. Yanagita had passed on his cold to me, while he awoke feeling right as rain.

We departed the inn at 6:30 a.m. The inn keeper had warned us the heavy rains would continue into the day and evening, but we were determined to get our start. Furnished with traditional straw raincoats and tucked under the protective cones of our sedge hats, the four of us splashed through the puddles to Sengen shrine where at a teahouse we found a team of horses and a cart awaiting us. The roofless cart muddled along the trail. Light rain drizzled down over us, tapping and popping on our sedge hats. Nodding thistles greeted us at the base of the mountain: violet, doubled over and looking chilled from the rain. Squirrels squabbled. Songbirds birdsonged from the stretchy pines and larches. The trunks of the trees were as straight as pool cues.

The terrain grew rocky upon our ascent. By the time our cart hit the first of the ten stations along the mountain trail, despite our raincoats and hats, we were soaked through. I felt the cold in my chest and head and tried to neutralize it with extra slugs of tincture. There was no mention of returning to the inn. The nine or ten-hour Fujiyama hike takes weeks to plan. It’s mostly on foot, you see. The horse carts will only get you to the second or third station. There are no cable cars—you hike it all the way to the top. There’s a certain pride amongst the Japanese for things like this. Especially when it comes to Fujiyama. An allergy to quitting, if you will. No sir. When you embark on a Fujiyama hike, you turn back for nothing.

We took tea at the station hut and chewed barley candy on a stick. The huts lining the trails were nothing more than rude shelters composed of lava blocks and plank roofs low enough to decapitate a fellow upon entry if he’s not paying attention. Sogabe got his walking stick branded with the station’s emblem while Yangita, Marbashi and I warmed ourselves over a brazier. My barking knee and deteriorating health called for yet more tincture slugs, which eased my distress: loose bolts tightened, hot spots cooled, cold spots warmed. Mellow violins stringed through me, re-tuning my body into a series of perfect fifths.

Opium. It has the power to set you right. The irony, of course, is that the righter you get, the more wrong you become.

We continued in the cart up the slope along the muddy switchbacks. The rain was really pounding now, coming at us sideways, into our faces. Marbashi was trying to cover his and Sogabe’s face with a newspaper he’d brought. Yanagita held an open hand in front of his, a useless gesture to keep it dry. The forest path soon morphed into a black stew of cinder and mud. The rain kept up. Marbashi knew of a flood basalt just off the path, and he and Sogabe convinced our horseman to stop while they collected some lava stones for our friend in Tokio. The stones were oblong, like small American footballs, a result of whirling through the air hundreds of years ago during the last eruption. An hour later at station two, our horseman told us the horses could go no further because of the slippery path. Marbashi argued that we needed to keep them until at least station three, but the horseman refused, so we continued on foot over the wasteland of bubbly rock and cinder.

The rain eased; the trail grew steeper. The next station loomed close, but it took us over an hour to reach it. I worried my constant hacking and coughing might spark an avalanche of volcanic slag tumbling down the mountain. My fever felt more pronounced with every step, destabilizing my equilibrium. With the higher altitude, breathing had become something of a wheezefest. With my snookered knee and my head growing more and more congested, I conceded several more slugs of the old brown and sweet. For most of the ascent, I’d been quietly arguing with a trio of apple-sized Prussian acrobats of whom I was convinced had stolen my toothbrush. I couldn’t tell if my disorientation had been due to the laudanum or my fever.

We reached station five by 4:30 and decided to stop for the day. The hut was an uproar of slurps and lip smacks from sopping tourists bolting back plates of curry sold by the owners of the hut. Many tourists, we learned, had already tried to make it to station six but were forced to turn back due to the rain. Fujiyama seemed utterly resolute in its efforts to keep us from witnessing the sunrise from its peak. Sogabe and Marbashi disappeared outside the hut for a while.

“You look ready to keel over,” a voice said to me.

I looked up from my plate of curry. It was the younger missionary I’d met earlier. The one who’d said she was ill.

“I may have already capsized,” I said.

“Shall I put you out of your misery?”

“Ha,” I said, assuming she was joking.

Then, her face grew serious: “We could finish this together.”

As she said this, she patted a brown leather satchel dangling at her side. It seemed as if she wanted me to think that this was where she’d stored her illness, and that she could share it with me if I wanted. In the spirit of witty repartee, I attempted a snide retort, snickering and stating that if the apocalyptic weather continued, this may very well be a final trip for us all. The missionary pursed her lips and thought about this. A clanging pot drew my attention, and when I looked back, the woman had disappeared.

Sogabe and Marbashi returned. “Look,” Sogabe, the younger of the two, said to me in Japanese, holding up his new walking stick. Its black station brand was still smoking. Marbashi moved to the other side of the hut and sat by himself, sulking about something.

“What’s wrong with Marbashi,” I said in Japanese (Sogabe’s facility with English was not up to the pedigree of Yangita and Marbashi).

Sogabe waved me off, irritated: “Nahh”

The four of us settled in for the night in the crowded hut with the rest of the stranded tourists, sleeping side by side on the damp floor mats like the fish at Uogashi fish market: tidy rows, heads and tails facing the same directions. I lost sight of the missionary. The rain sounded like marbles showering onto tin. Someone was scooping out my chest with a spoon. I couldn’t sleep. Sogabe mumbled at one point that it didn’t look like we’d get to see the sunrise this trip. I couldn’t dispute that. Another opium hallucination had me cursing at the bobbing wick of a kerosene lamp hanging on a beam. A tiny face had appeared in the flame, smirking, laughing at me. Another spiritual low point followed. My addiction. Where was it leading me? Despite my steadfast commitment to my anthropological endeavors, I knew my career was in jeopardy. Chicago University’s Quadrangle Club had been rife with suspicious looks from my colleagues. Jeers, whispers over cocktails of “the addict” Professor Wozniak. They all suspected. Yanagita, Marbashi and Sogabe likely had not been fooled either. Why, I thought, am I doing this to myself? What was my end game?

We made station six the next morning in just over an hour and rested for twenty minutes. The rain and wind had died down by now. The sky looked frazzled, as if all that rain had taken its toll. My cold had leapt a floor up from my chest to my throat, rummaged around for a while, and then ascended another floor to my head. It settled there, in my head, for the remainder of the trip. Before we left station six I tried to make an entry in my journal, but my hands shook so convincingly I gave up. On the way to station seven a deck of grey clouds reshuffled, exposing the sun, and I started hallucinating that the sun was screaming down at me—literally screaming—with a male, aggressive shout, as if someone had dropped a brick on its sunny toe. The mountain exhaled soft mists called kiri that warmed the bones, and we got our first good bird’s-eye look at the cloud cover below. We couldn’t see much landscape at first, but in the distance the Hakone Mountain range was visible, the dark mountain peaks rippling through the clouds like the backs of whales breaking the surface of the water. The clouds disbursed, and we spotted the farmland below, giving us the full map of the wrinkled and green Hakone mountains.

We pushed on to stations eight and nine and passed a party of boys from Yokohama Commercial School chuffing their way up the path in their stiff band collars and pointed military caps. I’d not seen the missionary since our station five encounter. Sogabe and Marbashi walked apart and spoke little. I got the feeling they’d had a spat. I asked Marbashi where the lava stones were. “There,” he said in Japanese, pointing down the mountain. His face maintained a strained look as he spoke.

I asked Yanagita again what he’d planned for the summit, but he only shrugged and told me I’d have to wait. Having now passed the kiri mists, the thinning air grew so frigid it could beat out the worst Chicago winter. Our damp raincoats only served to sponge up the cold. You could see your breath hovering in front of you and then feel it warm on your face as you passed through it. An opium itch thrust its saber. I parried with several gulps of tincture. I could still hear the aggressive shout of the sun—arrrrh!—thundering down from above. By now, my cold had taken over my body so completely that every step I took, every sound I heard, felt as if I were operating under water. We ran into the two missionary women at the second-last stop. The younger one smiled at me and asked how I was doing. I lied and told her I was feeling better. We chit chatted. She had her hand in the satchel at her waist, adjusting whatever was in there.

“What do you want out of the mountain,” she asked me.

“I just want to see a clear sunrise,” I said.

She said that she was there to set things right. Then her companion pulled her away to meet one of the schoolboys who had a question about America.

We reached the summit just before sundown. White snows caulked the cracks and ridges. More football-shaped lava stones dotted the black sands. The only vegetation: doubled-over birch trees, looking ghostly and ragged with their shredded white bark. The top of Fujiyama is the size of a village. It boasts a post office, a police station, several inns and retail shops, and scores of Shinto shrines. The day had managed to fight off the rain, but the storm clouds above and below had held their ground and looked ready to mount another assault. The summit was swimming with tourists purchasing postcards, amulets and seals for their walking sticks. Marbashi wanted to see the crater before the rain started again, so the four of us joined the crowds and shuffled our way around the lip of the crater. More winds. My head was so wooly, my equilibrium so unstable, I stumbled and nearly fell in. The crater resembled a lake sucked dry of its water—deeper than the tallest building and as wide as a football field. The vertical sides were sunburnt with oxidized olives and reds and lemon yellows. An odor of sulfur wafted up—vapors venting from the black sands below. We followed a trail that descended partially into the crater itself and stopped at the Kimmeisui hut where a white-robed priest sold water that had been filtered through the igneous sands. “Look,” Yanagita said, pointing at something on a table near the priest. It was a basket of what looked like smooth balls of black coal. Eggs, baked in the volcanic sands. We each bought one and ate them as we circled the rest of the crater rim, their black shells giving way to a rubbery white when cracked open.

By the time we finished our crater tour, a soft drizzle misted the air, and the sun had already set. We trolled inn after inn to secure a room, only to be turned away at each one—they were all full. The rain started back up. We ran into the two missionaries along the main road. They were also stranded with nowhere to stay. Marbashi and Yanagita covered their shoulders with their grass raincoats. Finally, one of the inns relented via a Yanagita bribe, and offered us and the missionaries two rooms. The women thanked us and retired to their room while the four of us crowded into ours and ate the conch stew the innkeeper brought. I’d already used up two thirds of the laudanum I’d packed for the trip and had to be careful. Yanagita was writing a postcard to his wife and two children. Sogabe and Marbashi played a game of mahjong. They were laughing now and seemed at ease with each other again. By eleven o’clock I was quaking so bad from chills I couldn’t sleep. I went for water at the communal sink near the front desk and saw the dark-haired missionary sitting in a lobby chair alone with her satchel. Her eyes were closed, and I assumed she was sleeping. I walked past her, trying not to disturb her.

“You can’t escape,” she said, her eyes still closed.

I stopped. “Excuse me?” I couldn’t tell if she’d been speaking about herself or me. She said nothing in response, so I assumed she’d been talking in her sleep.

I turned to the sink and drank. When I turned back, she was gone.

Back in the room, the windows rattled with Yanagita’s snoring. After dosing with several abrupt slugs of laudanum, I realized Marbashi was gone and Sogabe lay under his blanket, sobbing. Another spat? I began to question the nature of their relationship. Both were unmarried and getting on in years. They seemed to always be together except when arguing. It didn’t take a genius to put two and two together. Lover’s quarrel aside, I couldn’t help but envy them. Even in the depths of their squabbling, they still had each other. My life, in contrast, seemed as fractured and detached as my half-chowdered knee.

Outside the window, high above the mists, a full moon popped red against the black sky. The rain and winds had stopped again. I drifted in and out of sleep, my head wooly and pulsing with images of the missionary sitting in the chair with her satchel. What did she want? What did she mean by “escape?” My throat felt baked dry. My nerves darted. I couldn’t help but feel that a sinister motive was afoot. Was I just being paranoid? Therein lies the nature of the addict, indeed. Whatever glories sustained by riding the comet tail of an opium high, the side effects always added red to the ledger. It was inescapable. I knew this. Why, I thought, must a valley always follow a peak? I wondered this and longed for a world of stairs. Nothing but valleyless summits. Then I realized that stairs eventually stop going up, and ultimately, we all must come down.

I rose just before sunrise, feeling as gutted and grey as the skies the day before. It was still dark outside. Few stars poked through the clouds. Marbashi had returned in the night and was sleeping beside Sogabe, but now Yanagita was gone. I asked the two of them if they wanted to join me to see the sunrise and Sogabe moaned that he was too tired. Marbashi pretended he was sleeping, but I could tell he was awake.

My head still thumping, I found a small path leading to the faded white torii gate, a double-necked, double-legged “T” jutting lopsided from the sands, the best vantage point from which to view the sunrise. The rain had stopped, the red moon gone. The waning stars shed enough light to spot the outline of the clouds below. Lanterns bolted to posts lit a trail peppered with volcanic scoria. Much of the mountainscape in this spot was scarred by the hardened lava flows, wrinkly and grey like the skin of an elephant. The climb to the torii was steep, and I had to brace the lemon knee with my hand to ascend the final paving stones. I heard nearby voices and crunching footsteps every now and then, but they sounded far off—other tourists, heading to the lookout points.

I was the first to reach the torii, which was buttressed by a railing that overlooked the clouds below. I closed my eyes and pinched the bridge of my nose to try to stifle the pounding in my head, and when I opened them again, there she was, the missionary, standing in front of me. Her satchel wasn’t dangling by her side this time. She’d removed it from off her shoulder and was holding it in her hand now. She was staring at me. Her cheekbones stood out on her face and in the mist, her head looked chalky and narrow, like the skull of a deer or an antelope Her mouth was clamped tight, as if straining to hold back something from jumping out.

“Are you here to kill me,” I said.

She didn’t answer.

“What did you mean when you said you’re here to set things right?”

She reached into the bag and pulled out what was inside. It was small enough to fit inside her fist. I couldn’t see what it was exactly, but I could tell something was there. The bones of her fist were moving a bit. Whatever she held was alive and wriggling. She held it away from her to get it as far from her body as possible. She approached the rail in front of us. She wasn’t looking at me anymore but out into the dark clouds beyond. The closer she got to the rail the more the thing in her hand wriggled. I still couldn’t see what it was, but little black blobs of it were squishing up through the seams of her knuckles. She stopped just short of the rail and I saw her face, wet with tears. I’m not sure if she was weeping or if they were from the strain of trying to hold the thing in her hand.

“I’m frightened,” she said.

“You can do it,” I said.

I don’t know why I said that. I didn’t understand what was happening. But I realized then that whatever she held in her hand was somehow linked to me. She was looking at me again.

“You have to do it,” I said. “Throw it over. Get rid of it.”

I told her I’d stand with her while she did it and put a hand on her shoulder. She closed her eyes and cocked back her hand. My heart was pounding, leaping almost into my throat. The sky had lightened now. The woman paused with her arm extended back, her eyes still closed. I told her again that she could do it, that she had to.

“Now!” I said. “Do it!”

A wave of coppery light advanced on us, casting the woman in silhouette. I turned away from her to peer over the railing. The sky paled. Below us, a sea of white, stiffened smoke appeared. A halo of orange and pink rose up out of the clouds. Then it fattened and flushed citrus, then yellow, then almost white. It was so bright it made you squint. Spikes of golden light came at us, and then the smokey clouds opened up to the landscape below, steaming with morning mists: the accordion folds of the Hakone Mountain range and Odawara and Suruga Bays, their blue waters looking hammered flat by the sun; the long, smooth chops of green farmland; the lovely necklet of lakes.

I was about to plead with the missionary one more time to throw whatever was in her hand over the rail, but when I turned back, she was gone. I looked down the path to the torii, across the rest of the mountain top. Nothing. She was nowhere to be found. Groups of tourists were streaming up to the torii now, taking up the spot where the missionary had just stood a moment before. The mists had cleared. Before I realized it, tourists were lined along the torii rail and beyond, all the way across the summit, packed ten deep, watching the sunrise. Some said it was the finest one they’d ever seen. I continued scanning the crowd for the missionary but couldn’t see her anywhere. I looked over the rail, hoping to find some evidence that she’d thrown over the side whatever had been in her hand, but all I saw were ash, stones, rocky slopes. I was about to return to our room when the screech of some otherworldly bird split the sky, and someone came shooting past, naked but for a loin cloth:

Banzaiii! Banzaiii!

It was Yanagita. He was sprinting along the path, weaving through the tourists, waving his hands, slapping his shoulders and chest, shouting to the skies.

This was his surprise.

The crowds turned from the sunrise and watched him. He reached the end of the path, turned, and sprinted back in the same direction, still shouting as he ran. Dirt spat out from under his bare feet. Some tourists in the crowd started hooting, encouraging him. When he passed a third time, many joined him in his shouting and cheered him on.

Banzaiii! Banzaiii!

He kept this up for some time, sprinting back and forth along the summit of Fujiyama, shouting, running so hard his feet seemed to drift up and off the path.