As they wait for their food to arrive, Becca reaches across the table, lacing the fingers of her right hand through those of her boyfriend’s left.

“You’re fidgeting again,” she tells him.

“Sorry,” he says. “People keep staring.”

“No, they’re not.” Becca pauses, looks around, and sighs. “Maybe someone is. Who cares?”

“I mean, I don’t. Not really. Except, I do. A little. Only sociopaths don’t care what anyone thinks,” he replies, self-conscious still.

“Fine. Care what I think. Care what your daughter thinks. Not these strangers. Bastards every one of them.” She grins and adds in her best put-on Tennessee twang, “You know we just couldn’t help but fall in love.”

At this, he laughs. She does always have a way of keeping things light, of giving him perspective. That’s part of why he is with her, why he’s committed to this relationship, the world be damned. He must admit, it feels good to be falling in love again after so many years. That’s what this is, he’s believed for some time now – love. Not just sex. Great sex, to be sure. But not just that. He likes being with her. Listening to music, going to the movies, getting dinner after a long day at the plant. Love.

He also understands, in a way she cannot, how her choice to be with him is almost certainly the wrong one. Someday, he may have to make decisions for them both. If he must go for her to be happy, he will go. She will never be the one to sever the tie. For now, this is what she has chosen, and he has decided to honor her choice, however misguided it may be.

Though he worries on it far too often, he cannot say for how long this will last. At least until the salads arrive, he is sure.

Tonight, they will have their meal – whole lobster for him and salmon for her – then drive downtown to window shop as best they can in an area now dominated by legal and dental offices. After a short stroll through his declining, but still charming, hometown, they will return to his place to make love – if all goes as planned, of course. In this she never disappoints, though he often worries his performances do not pass muster. He is more experienced, and she never complains. In fact, she seems to enjoy their lovemaking very much, often being the one who requests a reprieve when he could go on. No small part of this, he is sure, has to do both with his physically demanding job and the gym membership he does not let go to waste.

But in the darkness, when she lay sleeping, he will wonder what business he has with a woman so beautiful, so kind, so full of youth.

To this, he has no answer.

* * *

Joshua Wagoner – father of Julie, personal handyman for Waymore Hall room 619, and his daughter’s valet – stepped from the suite’s shared bathroom where he had been setting out an uncountable number of toiletries, as ordered, just as the final syllable of her call receded.

“Daaaaad!” Julie had yelled, dropping the bed frame to the floor, unassembled.

“Honey, you don’t have to yell. I was thirteen feet away. And you said you wanted to do this yourself. That’s why you put me on Bath & Body Works duty.”

Smiling, in spite of her frustration with the stupid bed, she replied, “It doesn’t fit. I think there’s a lug nut missing or something.”

“Lug nut? I don’t think so. Missed a couple of episode of Bob Vila, huh?”

“Daddy, don’t be racist. You can’t just say that Mexicans build everything. You’ll get me kicked out of the dorm.”

Joshua sighed and explained This Old House to his daughter, sufficiently enough she admitted he wasn’t being racist on purpose. After looking at the bedframe that would soon loft Julie’s twin above its companion, something the future roommates had agreed to months ago on Snapchat or some such thing, Joshua declared they had all the lug nuts they needed but were short a couple of other pieces of hardware.

“I think I can run down to the first floor and get them. They said something in parent orientation about keeping some spare parts in all the dorms just in case. And ‘in case’ seems to have arrived.”

As the elevator landed on the ground floor, Joshua realized he had no idea where to go. He had made the assumption these mythical spare parts would, for some reason, be located here. But this was a big building. They could be anywhere.

Not wanting to look too much like a dad, he made a loop around the lobby, feeling sly, perusing the flyers and handbills plastered to the walls. The announcements covered the first meetings of every university club imaginable from the College Republicans to the “Smoke ‘em if Ya Got ‘em” club whose circulars looked hand drawn and rather floral. He hoped Julie could resist joining either of those particular groups.

Nodding to a few passing students and their parents, hoping he fit in, Joshua decided maintenance rooms must be camouflaged these days, not to threaten some of the upper-middle class parents with the prospect of actual labor. Heaven forbid.

On his third or fourth pass by the reception table, the girl on duty finally spoke. “Excuse me. Mr. Wagoner? Are you finding everything okay?”

Slightly embarrassed, and surprised, Joshua could manage little more than a sheepish shrug accompanied by his first blush in many years. He did not know what had stopped him so suddenly in his tracks. Her abruptness? The Townes Van Zandt T-shirt she wore? That was a surprise. Getting called out for his clear incompetence in finding his destination? Less of a surprise, he supposed.

“Hi. I’m Julie’s dad. Julie Wagoner. You already knew my name. How did you know my name?” Joshua sputtered, immediately regretting he had ever learned to talk.

“Hi, Julie’s dad. I’m Becca. See? Name tag. Just like yours. What can I help you find?”

“My daughter and I are putting that damn loft together and ran out of screws.” That’s what he meant to say.

“My daughter and I have been screwing-” is what he actually said before catching himself and briefly contemplating whether or not he could make it to the one open elevator before the doors shut. Riding it to the top floor and jumping out of a window was not entirely out of the question.

Becca dropped her chin in mock surprise until she could no longer hold back a belly laugh, deep and robust for a young woman her size.

When she regained most of her composure, she said, “It’s okay. I get it. You need Room 001. The maintenance room. Here, I’ll draw the route to get you there on this.” She held up a small map of the basement level xeroxed in black and white, clearly meant to guide clueless parents to their destinations.

He thanked her and took his leave, sans most of his dignity. Once he made it to the basement, finding Room 001 was a cinch thanks to Becca’s map, though the bare walls and lengthy halls felt labyrinthine. The door to the room was one of those split jobs, with the top half swung open and a little counter built into the bottom section. A sign said, “Please ring for service!” so he did. A short man dressed in the long-sleeved, crimson work shirt, the university’s ubiquitous custodial and maintenance staff uniform, eventually appeared from somewhere deep in what was most certainly a second labyrinth of parts and supplies. The patch on his shirt read “Gary,” and with only slight aggravation, he handed over the necessary parts needed to complete the lofting project – screws along with a couple of connector plates. Gary wished him luck (he might have even meant it), and Joshua headed back towards the elevator.

When he found it again, only slightly troubled in reversing Becca’s directions, Joshua punched the button to go up, the only one on the wall-plate except the fire alarm. When he stepped inside, he realized the LOBBY button was already lit. Rather than heading straight back to building bedroom furniture, he decided he might as well stop by the front desk and tell the girl in the Townes shirt of his success.

One floor up, he exited the elevator and moved across the lobby. At the desk stood two other sets of parents, waiting. Nothing to do but join the queue, he thought, giving himself dad points for the rhyme.

When his turn came, he stepped forward, jangling the parts he had secured from Gary. “Hey, thanks for the help. Got just what I needed.”

“You’re Julie’s dad, right?” she said.

“Oh, you’ve met her!” he exclaimed, immediately understanding how stupid he continued to make himself look in front of this girl who must have been every bit of nineteen.

“No, not yet.” She laughed her deep laugh again. “But I remember you, so I’ll keep an eye out for her. And you didn’t have to wait in that line just to thank me, but I appreciate it.”

“I have to be honest. It wasn’t just about that. I saw your shirt earlier, and I’m curious. Do you really listen to Townes or did you just buy the shirt at some retro, hippie-redneck store?”

She looked him over as though he had just called her a whore. Then she smiled again. “That’s such a Boomer thing to ask, Julie’s Dad. How about this? Helping all you parents makes me feel like I’m ‘Waitin’ Around to Die’?”

“Nice.” He appreciated the reference to one of the maestro’s saddest songs. “You can call me Joshua, by the way.” He pointed at his shirt as if he had just discovered his name pinned there.

To her credit, Becca acted as though this were new information to her as well. “Thanks, but I like Julie’s Dad.”

Feeling a bit uncomfortable about the presumably unintentional double entendre, he changed the topic back to music with as much haste as he could muster. “Do you like Guy Clark, too?”

“As a matter of fact, of course. Guy, Steve Earle, Townes. All those guys. And Emmylou. Nanci Griffith. Lucinda. Dolly, too, of course.”

“I’m impressed. I hate to admit it, but I really thought kids your age just listened to Taylor Swift on repeat.”

“Not me. I had a teacher in high school who turned me on to the good stuff. The real stuff. Only the badasses do it for me.”

“My apologies. Sincerely.” As he turned to walk away, he thanked her again, for what could have been the fiftieth time. Only a couple of steps from the counter, he stopped and turned backs towards the girl, unable to resist taking one parting shot to make up for the several feet he had inserted into his mouth earlier. “I’m not a Boomer, by the way. How old do you think I am?”

As he rode the elevator back upstairs in preparation to loft a bed with nothing more than the help of an eighteen-year-old who did identify as a Swifty, Joshua realized the reception girl had just given him a little hope for the future. Or at least the future of good country music.

* * *

With Julie gone, the house fell quiet, and Joshua realized he would have to find new rhythms in life, especially in the evenings and on the weekends. He worked a standard nine-to-five at the automotive plant in town which left his free time to him.

In a former life, he had graduated college with plans to become a P.E. teacher, but back then, openings were few and factory money was pretty decent if a guy could hire on as a skilled tradesman. With no luck landed a teaching job the summer after graduation, he got lucky and quickly found an apprenticeship in sheet metal. While it had not made him rich, not even remotely so, he had been able to provide for his daughter, and his wife – once upon a time. He found satisfaction in making and repairing things, with lofting twin beds his newest acquired skill.

A few weeks into school, Julie had come home only twice, both times so he could help with her laundry. They lived so close to the university, just a half-hour up the highway, many of Julie’s friends had enrolled there as well. She simply saw no reason to come back to their small town when, at school, she had it all – independence, lots of new friends, and many of her old friends. As much as he missed her, Joshua encouraged this, believing these years of eating pizza in the dorms, running through the campus fountain at midnight, and learning to navigate the ups and downs of living (mostly) on her own would shape the woman she could become.

Most nights in his newly-emptied nest looked and felt the same. Come home from work, heat up some cold Chinese take-out, and binge on a few episodes of Barney Miller. He had already rewatched all eleven seasons of M*A*S*H since the start of school. He couldn’t, after all, spend all of his time jerking off to old pictures of Suzanne Summers on the internet.

Part of this nightly ritual, after he had placed the dishes in the dishwasher, but before be resumed his sitcom marathon, included checking his Facebook account. Rarely did he see anything of note, but the algorithm knew him well, and the scrolling sometimes felt interminable. One night that fall, he noticed he had missed a message request. When someone who isn’t on a user’s Friends list sends a message, FB puts it in “Message Jail” until the user bails it out or decides to leave it to rot. Most people rarely check this folder because so few items of worth ever end up there.

On this particular evening, Joshua had decided to take a look, maybe from boredom or an increased tolerance for risk since his daughter was not at home to tell him how stupid he was for looking at strange messages. In either case, when the name Becca Moore appeared, he experienced no flash of recognition. At no point did it occur to him that this could be a bot or spam or some other attempt to steal his credit card information Then he noticed the profile picture, even in its thumbnail form, clearly showing the album cover from the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s first Will the Circle Be Unbroken album. Russian bots tend to prefer large-chested women, scantily clad. As he clicked on it, something about the first name poked at his memory – not a sudden stab of recognition, just a gentle tap to loosen up some currently inaccessible grey cells.

Dear Julie’s Dad,

I hope you don’t mind me writing you like this, that is doesn’t seem creepy or anything. I haven’t met your daughter yet. But I sometimes sort her mail. Part of the job. A few days ago, I saw you had sent her a package. Chocolate, I hope! Anyway, I thought I’d take a look and see if you were on FB. Looks like you are! I don’t meet too many people who like the music I like, so I just wanted to say, if you have any good suggestions I’m game! I hope you don’t think this is weird or anything. But if it is, just don’t reply. And maybe don’t tell Julie. I definitely don’t want her to think I’m a creeper!

Okay, so if you decide to write me back, tell me about the best show you’ve been too. I’m not even 21 yet, so I can’t get to the good shows at the bars. But I’ve been to a few bigger venues. So you tell me yours and then I’ll tell you mine!

Hope to hear from you!

Becca

P.S. You didn’t even ask me what my favorite Townes song is…

The courage that must have taken. Joshua imagined her sitting, clearly nervous, at her computer composing the message, hovering the pointer over the send button, then pulling away, over and over until she finally closed her eyes and mashed down on the mouse or trackpad or whatever. In high school, he had experienced something similar when, one night, he tried to work up the nerve to call a girl in his class, dialing all but the last digit of her phone number, then hanging up. Over and over.

As he remembered that night, trying to make first-phone contact with his crush, he felt a bit silly. Of course this was not the same. No college girl would have butterflies over him. She just wanted to talk music.

He also realized the message had been in his folder for over two weeks. She must have thought he wanted nothing to do with her. If he were honest with himself, as he usually was, he thought it kind of cute and could very much sympathize. Not many of his friends enjoyed the music he listened to either. Liking unpopular music has its benefits, like elbow room on the stage at the local bar. But finding compatriots with whom he could share his passion for all things alt-country, folk, and roots rock … well, even his daughter had not developed any interest in what he thought of as the good stuff. He had taken her to the Beanblossom Bluegrass Festival a few times when she was little. She loved to dance to the driving rhythms of the string bands until she got old enough to be self-conscious. And cool. That was the end of that.

Joshua could not find it in himself to kill the enthusiasm of youth, so he decided he’d write her back, that it would be fun to have a pen pal.

Hi Becca!

Sorry I’m just now writing back. I didn’t see your message until tonight. Lame, I know. Just chalk it up to an old guy and his technology. I am going to send you a friend request so that won’t happen again. Sound good?

I love to talk music and I love to help people find new things. Tell me who you listen to now, so I won’t just be preaching to the choir.

Best concert…no contest. Willie Nelson, Murat Theater. 1997. First row, about two seats left of center. Played for two-and-a -half hours. No breaks. He was still touring the Spirit album and played all of that plus a LOT more. Nothing will ever come close to that one. Now your turn!

Again, let me know who you like and I’ll see what’s missing!

Thanks for looking me up. And I don’t think it’s weird at all. But, you’re right, maybe we don’t tell Julie, for now, that we’re pen pals. She’s not on FB anyway – too cool for social media old people use!

All the best, (Bonus points if you can tell me the reference!)

Julie’s Dad (aka Joshua)

P.S. What’s you favorite Townes song? Mine has to be, right now at least, “Marie.” They don’t come any sadder than that!

To his surprise, she replied almost immediately. She wrote of the Tyler Childers show she caught in Lexington the summer before. His songwriting and Southern growl seemed to excite her equally. Even if he was a Kentuckian.

He replied almost as quickly, enjoying the break from his recent routine. He confessed he knew of the man but hadn’t delved too deeply into his catalogue. He admitted this was a bit strange since he felt “Bottles and Bibles” to be one of the better songs of the 21st century, young though it was. Her pervious message had made it clear that she was not quite the novice she believed herself to be, or at least the one she portrayed to him. A little gloating felt appropriate.

Hello in There Julie’s Dad,

I can’t believe I know something you don’t! You HAVE to check out Tyler. He’s the best

young songwriter around. And you HAVE to let me know what you think! And I certainly listen to John Prine. He was one of the first singers Mr. Donaldson played for me. My gateway drug.

All the best to you, too!

Becca

A little impressed Becca had known the Prine reference, he gave her the benefit of the doubt she had not Googled the line. He did wonder a bit on that one line. “Gateway drug.” He assumed she had meant the man from Kentucky via Chicago, but could she have been referring to her teacher? He did not know her well enough to ask, and knew this was none of his business anyway. Nonetheless, he filed the question away for later. Maybe.

Throughout the remainder of the semester, the messages became daily conversations about the music they both loved. Eventually, he began to hear about dates gone bad or how papers and exams made college life, which clearly could have been fun otherwise, horrible. Since meeting women at his age proved to be nearly impossible, and he hadn’t written a paper in many years (decades), he couldn’t commiserate with her exactly, but he could provide a receptive ear, or eye, as the case may be.

Julie came home for Thanksgiving and then Christmas. School was going well, and she had made friends. Though this, too, was a tale as old as time. She had a million things (her words) to tell him about her new friends and how she still saw some of her high school “besties” but others were drifting away. A little morose about some of the shifting alliances, she also seemed to understand that this was the way the world worked, the college part of the world at least.

When January came, Joshua discovered she was staying in the same dorm room, though her roommate had moved back home to be closer to family and would commute to a local community college. A friend she had made from the same floor would be moving in. Joshua was just glad he would not have to rebuild the damn loft.

He didn’t hear much from Becca over the Christmas break, but once school started again, their correspondence picked up where it had left off. He telling her about Flatt and Scruggs, Bill Monroe, Leadbelly, and Bob Wills, along with a pantheon of other great musicians, songwriters, and ne’er-do-wells who picked and sang American music into creation. For her part, she soaked it up as if he were another professor, but one who did not make her write essays and whose class she could not wait to attend.

A couple of times, he met her at the Culver’s a couple of miles from campus to hand off CD’s, books, or vinyl records she wanted to hear and to reclaim what he had loaned her last time.

The idea of meeting was hers.

Joshua,

(okay, okay, I think the Julie’s Dad thing is a little played out)

Hey! I hit YouTube this week, and Spotify, to listen to some of your recommendations, but I can’t find some of those old Western swing songs anywhere. I know you said you had an old CD mix… I hope you don’t think this is weird but… could I borrow it??? I’d take good care of it and give it back, I swear. Just think about it and let me know, okay?. No hard feelings if you think I’m just a stalker, and I’ll try to kill you or something! HA!

Maybe I shouldn’t have said that…

Just let me know!

Becca

So they met, and continued to meet, periodically, Joshua even getting brave enough to allow these meet-ups to turn into conversations. They’d grab a booth in the back where they would chat about music (and school and boys – Becca drove those conversations with little assistance from him – though she did not seem to have much interest in college guys) while he would sip on an iced tea and she would down enough custard to give a bus load of soccer players brain freeze. Sometimes she would bring her own CDs, or more often a list of songs for Joshua to look up on the internet – something he was getting better at thanks to Becca’s insistence that this was where music now lived.

When it came to music, he preferred vinyl, or at least CDs. The music coming out of a digital device might not sound much different than a disc, but he could hold those in his hand. He owned an actual thing. Music in the cloud, or the idea a person had bought something which existed only on a hard drive, well, he supposed he would always be too old for those kinds of notions.

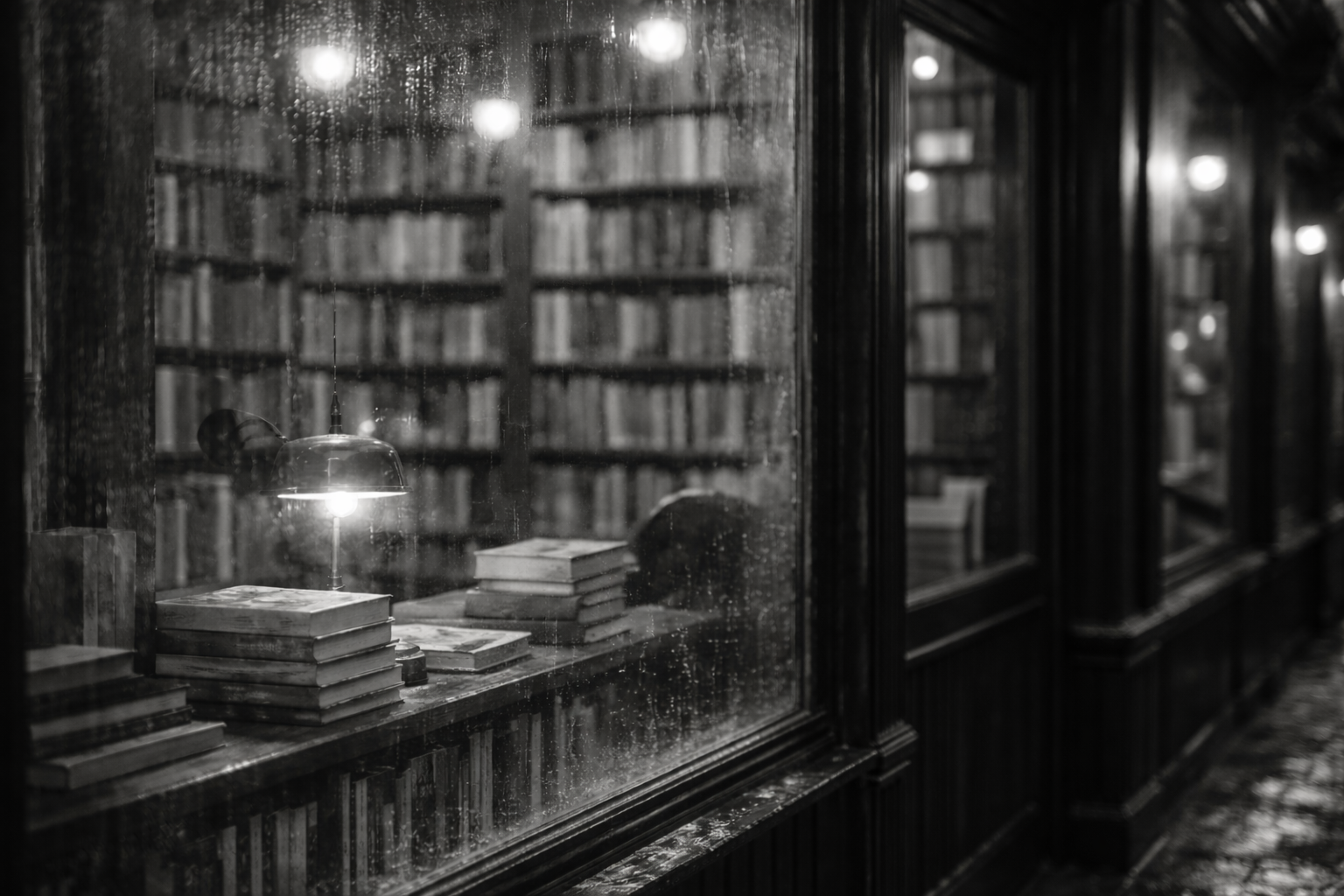

Just as much a Troglodyte concerning his reading material, Joshua liked to own physical copies of the books he devoured. He kept most of those he bought, but especially the books on music and musicians. He shelved the ones most important to him in the bedroom, identical live-edge boards suspended over matching lamps and complementary antique nightstands, all of which framed their queen-sized bed.

He could not help but think about the bed as “theirs,” though it had been his alone for many years. Longer, in fact, than they had shared it.

It had happened fast. So fast. Meningitis. Not something people die of anymore. Not usually. Not in America.

Except she had.

Kristen had chalked up a stiff neck to an exceptionally grueling workout the day before. It did not unstiffen over the next several days, and by the time she agreed to go to the doctor, the meningitis had become encephalitis. The doctors induced a coma to abate the swelling, but too late.

Joshua had raised Julie by himself with no more than a date or two every few years, though his heart never was in them. Most of them were fix-me-ups, arranged by well-meaning friends, his interest mostly in appeasing the matchmakers he knew cared about him. But Julie made him happy, and he had long known, while she still lived at home, he would not be able to share his time with another.

At the start of summer break, Julie moved back in and Becca went home.

The messaging did not stop.

* * *

Late the next fall, after resuming their Culver’s rendezvous, Joshua read online that a theater in Louisville would be screening Tamara Saviano’s documentary on Guy Clark, Without Getting Killed or Caught, for one night only. She had released the movie a few years back, but not widely in theaters, and not in his area at all. The movie did stream, but despite getting better with technology, Joshua refused to pay even more money for television than he already did. Since Louisville wasn’t too far – a piece down the road, but not too far – he mentioned this to Becca late one night just after the Culver’s staff had begun putting chairs upside down on the tables around them.

“I really want to see this movie. On a big screen. The book was fabulous. I can’t imagine this won’t be just as good. Better even,” Joshua said.

“Cool,” she replied. “I’d love to see it, too.”

“Let’s do it then,” he responded, his tongue once again outpacing his brain.

She said nothing, slurping the remains of her chocolate custard malt from the bottom of her large cup. The more she sucked, the surer Joshua was he had irreparably damaged their already unusual friendship.

Seemingly convinced there was no more sugar to be retrieved from the cup, she set it aside and looked up at him. “Yeah. Yes. Let’s do it. Let’s go.”

Joshua realized he had been holding his breath and managed a ragged exhale at her answer.

The showing was still several weeks off, but they arranged for her to meet him at his house, more or less on the way. He would assume the driving duties from there.

The next evening, he ran to campus to drop off Saviano’s book, so she could look it over before watching the film. Coming through the doors of the dorm where they had first met, he saw her leaning on the reception desk talking to the male student on duty. Her elbows propped against the counter, chin supported by her hands, and one bare foot kicked behind her, she did not see him enter. Joshua walked to the reception desk and tapped her on the shoulder, ignoring Mr. College completely.

“Hey, there. I’ve got your book,” Joshua said, turning his back to the boy whose conversation he had just halted.

“Thank you so much. I’m sorry you had to drive up here just for this. But I appreciate it. If I lived in town, it would be closer, I know. Kinda lame for a junior to still live in a dorm. But I need the work-study job, and being an RA pays the bills.”

“No worries,” he said. “You’re smart. Don’t spend any more money than you have to while you’re here.”

“For sure,” she said. “My parents help the best they can. They just can’t, much.”

“Well, here’s my contribution to the cause,” he said, handing her the book he had chauffeured to her door. “No charge.”

She smiled, thanked him, threw a fist bump, and told him she needed to get back to the floor.

Before he could turn to leave, she gave him a quick, almost-side hug. Joshua, feeling his face flush, patted her shoulder as she eased away. Being hugged by a pretty college girl felt nice. Especially this one. But confusing. His age did not even live in a neighboring zip code to hers. Hell, his age was closer to a zip code. He was not twenty, could not be twenty, did not even want to be twenty again. He’d taken all the tests he needed in life not involving cholesterol, blood sugar, or cancer. None of this cancelled the blush he had experienced during their hug.

* * *

When the evening arrives, their first stop was Salem where they ate at the tiny Thai restaurant just off the square for what might have been the best meal between Bloomington and Louisville. Also, probably the only reason to stop in Salem for anything short of car trouble.

During dinner, between bites of Pad Thai, Joshua had an inexplicable urge to question Becca about Mr. Donaldson, the teacher who had turned her on to the music she now loved. He couldn’t quite pin down why this occurred to him while wedged into this small booth, fumbling with chopsticks – an act he usually eschewed as cultural appropriation but insisted upon by his dining companion. Under what circumstances had this man, this teacher, introduced high-school Becca to his musical library? She had never betrayed a more personal relationship with him, but Joshua knew some teachers had influence over a certain kind of young woman.

He resisted the urge to ask, not wanting to spoil the evening before it had really gotten started, so he shoved more noodles into his mouth before his tongue could once again sabotage the conversation. Whatever had happened could not possibly matter to him as long as Becca had not been hurt. And to Joshua, she seemed more than fine. He did his best to banish the preoccupation from his mind and focused on his chopsticks and on Becca.

* * *

The movie was fantastic, everything he had hoped it would be. Becca cried several times, and if he were forced to admit it, Joshua might have confessed to squeezing out a tear or two of his own. On the return trip, they talked about it all – Guy, Townes, Susanna, Steve, Rodney, the whole lot of them. Even Uncle Seymour.

“I met him once,” he told her as they hit Mitchell, about fifteen minutes from his home and her car. “Guy, that is.”

“You’re shitting me! You did not. Why haven’t you ever told me this?” she said, shocked and clearly exasperated.

“I guess I just hadn’t thought about it. Or I thought it would sound like bragging. I don’t know.”

“Where? When? What was he like?”

“I mean, it wasn’t much of a meeting. I saw him back in the 90s at a little bar in Brown County. The Story Inn. I guess it was right before the rest of the country kind of rediscovered him. He was tall. Six-six. Six-eight. Whatever it was. He might as well have been Goliath. I shook his hand, and it just wrapped around mine like I was a little kid. My hand actually touched that silver and turquoise ring he always wore. Right about here.” Joshua pointed to a spot on his right hand as he steered for just a moment with his knee.

Becca reached over and pulled his hand towards her. She traced a finger across it as if she had possession of Guy’s hand rather than Joshua’s. She said nothing but, after a moment or two, enclosed his hand in hers as if to protect a holy relic.

For his part, Joshua, at first, got a kick out of her reverence for an event that had occurred years before her birth, the excitement of feeling this close to a master storyteller because he had once touched the hand she was holding. However, the longer she held him, the more self-conscious he became. For what felt like the first time that night (this couldn’t have been true), he noticed her outfit. The fall had been unseasonably warm, and she had chosen a pair of cut-off denim shorts and a loose-fitting tank top with a graphic depicting Guy and Susanna above the title of his song “Anyhow, I Love You.” Somehow, to Joshua’s way of thinking, Becca had pulled off the delicate combination of rootsy and cute. Very cute. And, he had to admit, sexy as hell. Feigning a need for his right hand, he broke the connection, smiled at her, regripped the wheel, and announced their imminent arrival at his house.

A block or two, and a turn or two, down the road, Joshua pulled into his drive and killed the engine. She thanked him for driving, and he thanked her for riding along.

“Go ahead and get your car started. It’s cooling off a little, and you’re going to get cold. I’ll going to run in and grab that Townes book for you. Do you want anything to drink for the road? Some caffeine maybe? It’s late”

“No. Thanks. I’ve got a cold cup of coffee in the cupholder. I’ll be fine.”

Inside, Joshua walked the length of the house to his bedroom where this particular book lived. Over his nightstand, he displayed the tomes by and about his favorite singer-songwriters. Moving his finger down the row past Shaver, Nelson, Cash, and others, he stopped and hooked No Deeper Blue, the fairly recent bio of the ne-er-do-well rake and rambler from Texas.

After pulling the book from the shelf, he leafed though it quickly to make sure nothing of import hid inside. Turning to leave, he started at the sight of Becca shadowing the threshold of the bedroom.

She said nothing but walked towards Joshua, standing as if someone had driven a spike through his head, down his spine, and into the floor. She placed his hand on her cheek, and he did not stop her. Her body was flawless. Relatively tall, her breasts more than filled out the tank top she wore, loose though it was. Her skin, fair and smooth – the elasticity of youth – glowed in the soft light emanating from the bedside lamp Joshua had switched on to look for the book. She slipped off her shorts revealing a small patch of downy hair, trimmed and neat. Reaching up, she removed his hand – his right hand, the one she had cherished in the car not twenty minutes earlier – from her face and placed it between her legs. As he slid his fingers inside her, she pulled the tank over her head, unhooked her bra, and dropped them both to the floor. As she drew close to kiss him, she felt his hardness pressing against her stomach through the khaki shorts he still wore.

Later, Joshua would think, Maybe I should have turned away. Some men may feel they would have stood strong, asked her to leave, escorted her to her car. This is a lie, or at least a rush to judgment never tested. In truth, he did not want to turn away.

* * *

The overhead fixture in the bedroom still shines with incandescent light. Long ago, I traded those antiquated bulbs throughout the house for the newer compact fluorescents. Cheaper to burn and longer lasting. In here, however, I prefer a softer light, cozying the room when the dark curtains settle shut. But tonight, the glow keeps me awake. Between the weight of her body and the trio of blazing suns above the bed, I have no chance at all. I try to close my eyes against the concerns of the evening, but they pinball through my head, eyelids flippers knocking them back each time they try to escape. I try to turn my attention to other things in the room, to find a distraction. There on the wall hangs a painting my grandmother gave me when I first got married. Two clowns – one smiling, one sad – holding red and yellow balloons. A grandma Janice original. On the floor beside the bathroom, an old pair of shoes I meant to throw away the last time I wore them but never did. A pile of clothes, men’s and women’s, just beyond the bulge my feet make under the covers. Flat-screen TV hanging on the wall at the foot on the bed above my Empire-style dresser, the top clear of everything except the for the statue.

Kristen found it at a thrift store when Julie was a baby. They gave it to me for Father’s Day. She placed it there, in that very spot; my first trophy for being a dad, she’d said, not knowing she would never celebrate another birthday – nor another Mother’s Day. After she was gone, when only Julie and I remained, the trophy stayed exactly where she had placed it that day, though I cleared off the rest of the mess eventually. A small shrine, I guess, meant to be in honor of me – in the end, a memorial for her.

The whalebone hue of the resin reflected the yellows of the incandescent illumination, giving it the look of a patina it did not possess. The midcentury, Buddha-like, middle-class man standing atop a pedestal, hair almost crafted into a combover, smiles so his complete set of Tic Tac teeth advertise his pride. His pants may be corduroy, or that could be a kilt lapped around the ankles of his stumpy legs. His tie would be a clip-on were it not cast in resin, his jacket the perfect complement complete with a pocket square to fulfill someone’s idea of a fatherly outfit. Though I cannot see underneath the coat, the shirt must be short-sleeved. On the right side of his chest, someone has pinned a blue ribbon, a visual reminder of the honor inscribed upon the base where he stands.

I look down the length of her body as she begins to stir against me, my right arm wrapped around her back, her right leg crooked over mine under the blankets, skin on skin. I trace my hand up and down her spine, and I can sense her returning to consciousness. We have been here many times over the past year. We have told Julie, who has made an uncertain truce with us both. Had she asked, I would have ended it with Becca immediately, but she did not.

Likely, I am an old fool, she broken in ways I cannot yet see. For now, I refuse to countenance either of these notions. At all. So here we are, still, heading towards a future no novelist could write with adequate realism.

I cannot in good conscience ask Becca to care for me in an old age I will see long before her. We have talked about this. Briefly. At twenty-two, she is a full-grown adult with free will, a powerful intelligence, and an impeccable taste for art and music. But without an imagination capable of envisioning this future. Experience is one thing I have over her, and I know where this path leads. For me. For us. To repurpose a line from Jason Isbell, we are not vampires. Most certainly, I will be the first to pay this price, and she will be the one left behind.

Then again, Little Jimmy Dickens married at fifty, his wife twenty-five. They would have nearly forty-five years together. So there’s that. The one thing beyond speculation is this: I do not want to lose her yet.

As I look back at the trophy I have never been able to store, or even move to another spot within this room, I feel one of her nipples begin to harden against the soft skin stretched across my ribs, and I read “World’s Best Father” for what must be the millionth time in my life. I cannot help but wonder if being here in this bed, doing what we have been doing this past year, has in any way put my claim to that title in jeopardy.

To this question, I once again have no answer.