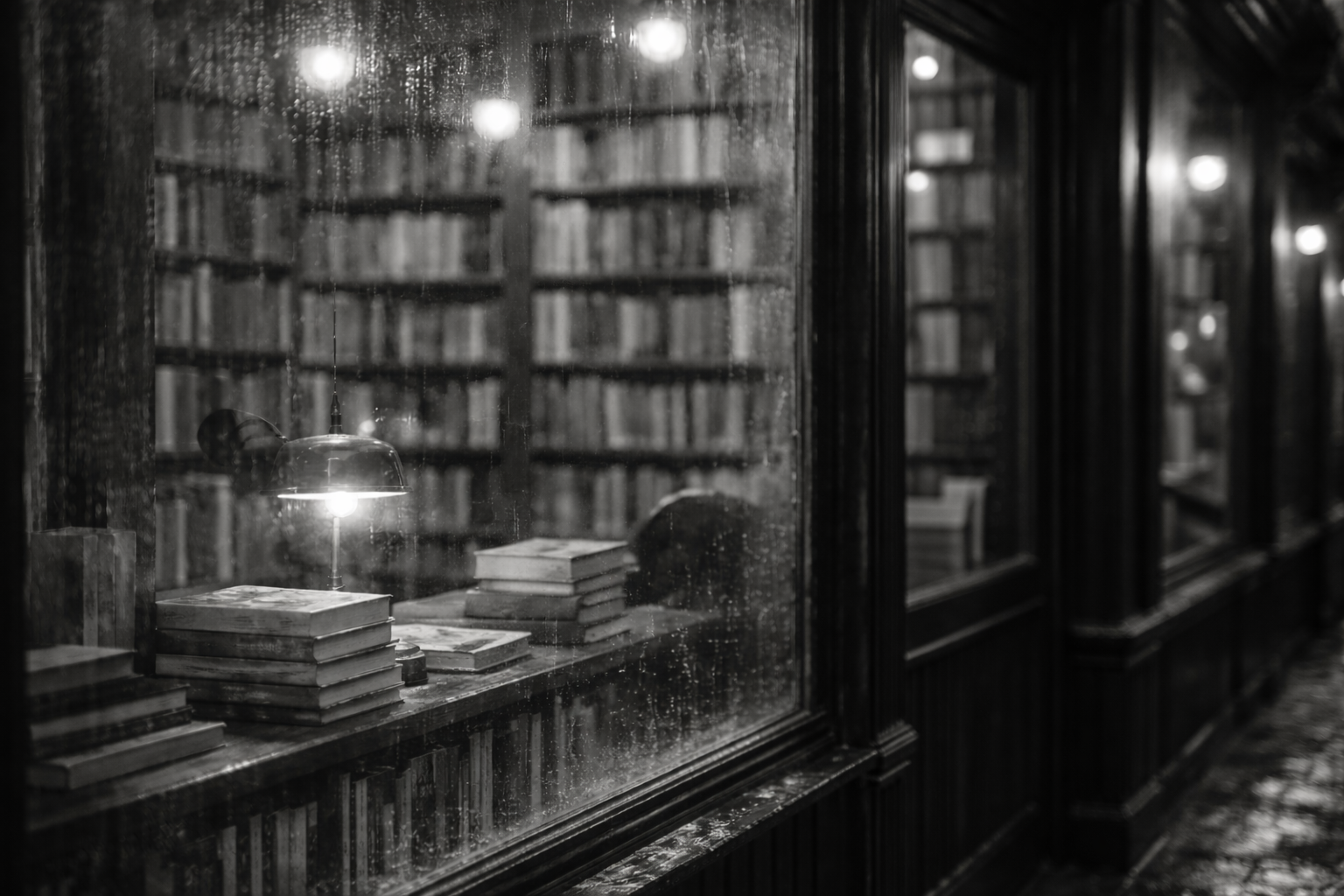

Writing in a mainland European manner is like sitting at a small café on a narrow Parisian or Brussels street. The table is barely large enough for a cup and a notebook. The chairs are close, sometimes uncomfortably so. The waiter speaks a broken English; not as an affectation and not as an apology, but as a simple consequence of the fact that English is not the language of the place. He brings the coffee without ceremony. Around you, voices overlap. Laughter cuts across conversations. Cups clink. Someone argues, someone reconciles, someone listens in silence. The street is loud, but it is loud with people. The space is limited, yet no one seems in a hurry to escape it.

There are no billboards above your head. No screens blinking for attention. Nothing explains itself. The names of cafés and shops are written modestly on their façades, as they have been for decades. They do not persuade you to enter; they simply exist. You are not guided, not warned, not prepared. You are expected to sit, to observe, to endure the density of the place until it begins to make sense on its own. European writing assumes this same posture. It does not clear space for the reader. It accepts proximity, friction, and the quiet pressure of things being too close together. Meaning is not delivered; it accumulates.

In such writing, sentences do not rush to reassure. They stretch when thought requires it and contract when it does not. Ideas sit next to one another without polite transitions. The reader is not told where they are going or why they should care. Attention is assumed to be available, and therefore treated as something serious. Difficulty is not a flaw to be corrected but a condition to be inhabited. One reads as one sits in the café; alert, patient, exposed to other presences that do not adjust themselves for comfort.

When I was studying in St. Louis more than a decade ago, I noticed something that struck me as deeply strange. Streets divided not by chance or history, but by design. Gated communities. Invisible borders. Entire neighborhoods separated by race, where people lived on one street and never wandered into the next. The separation was not symbolic; it was architectural. It was enforced by distance, by fear, by the quiet agreement that certain bodies belonged in certain places and nowhere else.

My aunt lives in New Jersey, less than half an hour from New York, and she never used public transport. Not because it was unavailable, but because it was unthinkable. Movement itself was privatized. The street was something to pass through in a car, not to inhabit. Encounter was optional, and therefore avoidable. She didn’t even know that Garfield had a train station.

In Europe, even the racists and those they despise are mixed together. They sit in the same cafés, stand at the same bars, wait at the same bus stops. They hear one another breathe. The hostility exists, but it exists inside the head, not in the street. The street does not protect anyone from the presence of others. It forces coexistence, however uneasy. This is not a moral achievement; it is a spatial fact. And from this fact, a certain kind of literature becomes possible.

European literature is born from enforced proximity. From the impossibility of sealing oneself off completely. From the daily friction of languages, classes, resentments, affections, histories, all occupying the same physical space. Thought, under these conditions, cannot remain clean. It cannot remain pure. It must account for contradiction without resolving it, for coexistence without harmony.

American-style writing reflects a different spatial logic. It is shaped by separation; by zoning, gating, distancing, filtering. Conflict is managed by removing contact rather than enduring it. This produces prose that explains itself, that clarifies its moral position, that separates good from bad with visible lines. It mirrors a world in which difference is sorted geographically and socially, and therefore need not be carried inside the sentence.

European writing carries the conflict within itself. It does not outsource tension to plot or resolution. It allows incompatible elements to sit side by side without synthesis, much like people who share a street without sharing beliefs. The text does not protect the reader from this tension; it reproduces it. Ambiguity is not a stylistic flourish; it is a consequence of living too close to others to simplify them.

This is why European prose can appear cold, dense, or indifferent to comfort. It is not indifferent; it is accustomed. It assumes that the reader, like the citizen, will encounter what they dislike, misunderstand, or resent, and will nevertheless remain present. The ethical weight of the writing lies precisely here. Not in declaring positions, but in refusing to spatially segregate ideas, emotions, or perspectives for the sake of ease.

To write in this way is to reject the illusion that separation produces clarity. It is to accept that the worst things people think remain inside them, not because they are resolved, but because they cannot be engineered out of sight. The page, like the street, remains shared. And this, more than style or technique, is the deepest foundation of mainland European literature.

From this difference in space follows a difference in imagination. Much contemporary American writing gravitates toward moral legibility. Characters are arranged so that virtue and vice remain visible, identifiable, and safely separated. Conflict is externalized, dramatized, and resolved through opposition. The reader is rarely left uncertain about where to stand.

European literature has long moved elsewhere. It wanders in territory where grey dominates, not as an aesthetic pose but as a consequence of proximity. Characters are neither purified nor condemned; their moral stature is not argued but perceived. Judgment emerges slowly, shaped by context, history, and endurance, much like the stone figures of kings, heroes, and villains that populate European squares; weathered, ambiguous, present without explanation.